Bruce Torres

Let's be alone together.

A FRANCHISE AWAKENS

Building a Galaxy Far, Far Away: The Story of the Star Wars Expanded Universe, Episode I

by Andrew Liptak/

December 14, 2015 at 12:30 pm

It was the moment that readers were dreading since news broke that George Lucas had sold Lucasfilm to Disney for $4 billion: the moment the Star Wars canon would be stripped down and rebuilt from scratch. The Expanded Universe that had sprung up from the ashes of the second Death Star was not going to lead to Star Wars: The Force Awakens.

After the theatrical release of Return of the Jedi, a larger story had emerged, revealing what happened to the Rebels and the remnant of the Empire in the wake of that “final” film. It grew through a myriad of comic books, novels, roleplaying and video games, and other tie-ins, arcing backward and forward in time, collectively becoming known as the Star Wars Expanded Universe.

The Star Wars Trilogy: A New Hope/The Empire Strikes Back/Return of the Jedi

On April 25, 2014, Lucasfilm and Disney announced the creation of a new “Story Group” responsible for maintaining and developing the overarching story of the franchise. The announcement meant that the Expanded Universe that had been building since the early 1990s would no longer be considered canonical, and that the upcoming films would rely on a new, coordinated mythos. The time between Return of the Jedi and The Force Awakens would be reconstructed with a new series of books, comics and games, and while the older Expanded Universe novels would continue to be published, they would exist under a new designation, “Star Wars Legends.”

Fans immersed in the Expanded Universe were disappointed: the characters and adventures that they had followed for so long were going to end. Others were more optimistic—the Expanded Universe had grown organically over almost two decades; there were entries reviled by readers, numerous dead ends, and stories that were at times contradictory or difficult to reconcile. Maybe a fresh start would produce a canon that would be easier to manage.

For some, the Expanded Universe provided the definitive post-Return of the Jedi story, continuing the adventures of Han Solo, Leia Organa, and Luke Skywalker and giving a spotlight to some of the movie’s lesser known players like Admiral Ackbar and Wedge Antilles, and introducing numerous new characters such as Callista, Mara Jade, Grand Admiral Thrawn, Corran Horn, and Dash Rendar, some of whom became as popular with readers as their film counterparts.

How did these stories pick up the Star Wars mantle and become such a phenomenon in their own right, and how did the Expanded Universe take shape—and change over the course of its life? The answer lies in the numerous authors and editors who were tasked with continuing George Lucas’s grand story into the unknown.

Star Wars Splinter of the Mind's Eye

Every saga has a beginning…

Star Wars had always been closely linked to novels. Star Wars: From the Adventures of Luke Skywalker appeared in bookstores in November 1976, marking the film franchise’s entry into the public consciousness. The novel was ghostwritten by Alan Dean Foster, who had been brought in by Ballantine Books as an experienced tie-in writer, and who drew from the scripts and concept art of the original film.

Following the success of the movie, Ballantine Books released what had been planned as a contingency: a story written up by Foster to become the basis for a sequel, should Star Wars prove to be only a moderate success. Instead, of course, Star Wars was a massive success, and Del Rey simply released Splinter of the Mind’s Eye in 1978 as a further adventure in the franchise. It became an immediate bestseller. “The world was hungry for any new Star Wars story,” wrote Chris Taylor in How Star Wars Conquered The Universe. “Children would reread the paperback until it fell apart in their hands.”

Splinter of the Mind’s Eye became the first inkling of further adventures in the franchise, and it was closely followed by several other novels from Brian Daley: Han Solo at Star’s End and Han Solo’s Revenge, each released in 1979, and Han Solo and the Lost Legacy, which followed in 1980. The Empire Strikes Back screenwriter Leigh Brackett had signed on to write a novel about Princess Leia, but shortly after completing her screenplay, cancer took her life, and that novel was never written. These tie-in novels showed that Star Wars wasn’t limited to the adventures, characters, and stories of the film: they provided the first glimmers of a larger world beyond what was onscreen, an exciting “expanded universe” in which the stories of the film’s central characters lived on after the credits stopped rolling.

Three more books followed in 1983, following another hero from The Empire Strikes Back and written by L. Neil Smith: Lando Calrissian and the Mindharp of Sharu. Lando Calrissian and the Flamewind of Oseon and Lando Calrissian and the Starcave of ThonBoka. Other adventures appeared in a line of comic books from Marvel.

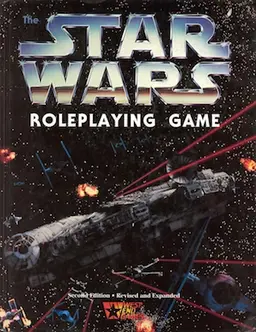

While these entries added to the Star Wars saga, the books and overarching story that we now know as the Expanded Universe truly have their roots in a small gaming company called West End Games. Founded in 1974 by Daniel Scott Palter, the company initially produced board games, before shifting to produce roleplaying games in 1984.

Bill Slavicsek joined the company in 1986 after answering a blind ad in The New York Times. He was brought on as a games editor, and branched into game design and development before the end of his first year.

Slavicsek had been a longtime science fiction fan and gamer. He read everything he could get his hands on, and when Star Wars hit theaters in 1977, he returned to the theater 38 times.

The same year he joined West End Games, the company worked to secure a license for the franchise. They had already worked with some high-profile properties: Star Trekand Ghostbusters, which ultimately won over officials at Lucasfilm. “I can only guess,” Slavicsek reacalled, “but I think the company pursued the license because the films had such an impact on all of us and they thought it would be a perfect match with the kinds of products that WEG did at that time.”

The West End Games team began working on a roleplaying game sourcebook, started by Curtis Smith, the head of the creative team. When management duties pulled him away from the project, Slavicsek ended up writing most of the book, assigned to the project when the team learned that he was a big Star Wars fan.

His approach was simple: “…to create material that worked with the stuff we saw on the big screen. I saw it as my job to explain what hadn’t been explained and to fill in the blanks so that Gamemasters could run campaigns.”

Roleplaying games, by their very nature, required the production of volumes and volumes of additional material, according to author Troy Denning, who worked as a game designer and writer for companies such as TSR and West End Games. A novel, he noted, only required what was necessary for the story at hand. Roleplaying games, on the other hand, required massive amounts of extra information for gamemasters to use.

The West End Games team had to produce an extraordinary amount of material for their games to work. They went to the original films, novels, scripts, and artwork, and were granted access to Lucasfilm’s archives to mine for information.

Between 1987 and 1999, West End Games produced numerous sourcebooks—notably the Galaxy Guides—for use in the games. “I don’t think that it would be an exaggeration to say that there wouldn’t be an EU without West End Games,” Denning noted.

Star Wars The Han Solo Adventures

The Galaxy Guides and other supplements were authoritative books that provided an enormous amount of raw material for Star Wars fans. Elements such as the names of alien species and their histories, the names of planets, weapons, spaceships, histories, and more were created for use in the games. Denning noted that working on them was a Star Wars fan’s dream: “My assignment was to take all of the characters in the cantina scene and to write their backgrounds and histories of their species. Whatever their common names are now, I made those up. ”

Slavicsek also wanted an element of realism for the games. “I wanted to smooth out any of the rough edges and make the place feel real. For example, ‘Hammerhead’ might be a fine name for an alien on a piece of concept art, but as I explained to my contact at Lucasfilm, that wouldn’t work as an official species name. No species is going to call itself something that sound derogatory or silly. So, in the fiction, Imperials and other elitists will call them ‘Hammerheads,’ but they call themselves ‘Ithorians.’” This philosophy was critical in shaping the tone of the materials that they were putting together. Star Wars stunned audiences by presenting a massive world that felt lived-in; the materials that West End Games was creating followed the same line of thought, and helped provide the context for what was seen on the screen.

Star Wars The Lando Calrissian Adventures

While there had been additional stories told in the Star Wars universe, it was the West End Games materials that really demonstrated to Lucasfilm officials the value of expanding their horizons. “[Lucasfilm was] extremely excited by the prospect of us adding to the existing lore.” Slavicsek recalled. “The RPG book began that process by expanding on a few basic concepts, including the Force and hyperspace travel, but it was the Star Wars Sourcebook that really opened their eyes to the kinds of details we could fill in to help explain their universe.”

The gaming supplements were adding something interesting to the Star Wars universe: it was raw building blocks for storytellers—at the time, gamers—to create their own tales. The West End Games materials became akin to an operating system upon which all Star Wars tales would be based.

Lucasfilm kept a close eye on what they were producing, ensuring that their creations were in line with the tone and intentions of the films. Everything was looked over by the company, and even George Lucas weighed in. “They reviewed and approved everything.” Slavicsek explained. “I could even ask George Lucas a few select questions during the process, as long as I framed them as ‘yes or no’ questions so he could fire back a quick answer.” Lucasfilm had firm rules in place, and suggested alternatives or asked the game makers to steer clear of certain elements, such as Yoda’s species and whether or not Stormtroopers were clones.

West End Games’ Star Wars line was extremely popular, becoming a major source of profit for the gaming company. In the years following the release of Return of the Jedi, there was an appetite for new Star Wars content from the general public, bolstered by persistent rumors of plans for sequel and prequel trilogies.

Star Wars Thrawn Trilogy #1: Heir to the Empire: The 20th Anniversary Edition

Troy Denning asserted that without the efforts of West End Games, the Expanded Universe as we know it wouldn’t exist. “West End Games was huge in establishing the EU before there was an EU. I don’t think that it would be an exaggeration to say that there wouldn’t be an EU without West End Games. The sheer amount of material created for a roleplaying game helped to establish the foundation for the EU and the books that game later on.” He went on to note that after while he was reading Timothy Zahn’s novel Heir to the Empire, he noticed that some of the species that he had invented for Galaxy Guide 4 had been incorporated into the text, something that he was very excited to see.

By the late 1980s, West End Games had done something unique: they had established the elements from which any fan could work off of to tell their own stories in the universe with some level of consistency. The story of Star Wars had ended with Return of the Jedi, and there were no concrete plans for additional movies. Without the efforts of Slavicsek and his team at West End Games, the universe would have simply ended.

Despite West End Games work, by the late 1980s, Lucas Licensing had begun to spool down its efforts: there were no new films planned, and slowly, it seemed as though Star Wars would slip away, fondly remembered by fans who had seen it, and by an even smaller group of fans who played their own adventures, using building blocks that had been written down.

However, the seeds for something greater had been planted, and were waiting for the right encouragement to blossom. More on that tomorrow.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

BRAINS AND THRAWN

Building a Galaxy Far Far Away: Heir to the Films (1990-1994)

by Andrew Liptak/

December 15, 2015 at 4:00 pm

Between 1977 and 1983, George Lucas’s Star Wars franchise electrified a generation, changed cinema forever, and created a passionate fan base. But with no new films in sight by the end of the 1980s, Lucasfilm began to move on from its science fiction properties. The grand space epic might have ended with the handful of short stories and reference materials had it not been for Lou Aronica.

In 1986, Lucasfilm eased up on the licensing campaign: Return of the Jedi had been out of theaters for three years, and at the time, Lucas felt he was done with directing and done with the franchise that had made him so famous. With the movies receding into the past, there didn’t seem to be a market for the action figures, comics, video games, and other tie-ins that accompanied the trilogy. It was time to look to new creations.

Shadow Moon: First in the Chronicles of the Shadow War

In the 1987, Lucy Wilson, the finance director in Lucasfilm’s licensing department, was promoted to director of publishing , overseeing literary offerings involving the company’s intellectual property. By this point, she had worked on a trilogy of tie-in novels for Lucasfilm’s latest offering, Willow, which would come out years later as Shadow Moon, Shadow Dawn, and Shadow Star. The last Star Wars novel, Lando Calrissian and the Starcave of ThonBoka, had been published years earlier, and “no one at Lucasfilm was thinking of doing new Star Wars novels in 1989.”

Wilson was attending a book fair in New York, working on unrelated projects, when she met with publisher Byron Preiss. He wasn’t interested in her ongoing projects, but mentioned that they should start looking at Star Wars novels instead—those would likely sell.

“That seemed like a really good idea to me. Having been at Lucasfilm, since before the release of the first Star Wars movie,” Wilson recounted, “I knew the impact it had and felt there were a lot of people out there who were dying for something new in the universe.”

She returned home and proposed that the company license a couple of novels. With the blessing of George Lucas, she began to explore her options. Out of contractual obligations, she approached Ballantine Books first, but they passed: they didn’t believe that they would be successful with no new movies on the horizon. Wilson then went through the company’s correspondence from publishers, and came across a letter from Bantam Spectra publisher Lou Aronica, written a year earlier. She remembered that she had been impressed by the company’s presence and offerings at the book fair, and gave him a call.

Aronica joined Bantam Books in 1979 after completing college, and after several years, took over their science fiction line. During that time, he shepherded number of books and authors that established Bantam as a major publisher of genre fiction: David Brin, Gregory Benford, and William Gibson, as well as well-established authors such as Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke. In 1985, he launched a dedicated genre imprint called Bantam Spectra.

As a publisher, he hadn’t been all that interested in working with licensed properties, as he had largely been disappointed with the Star Trek novel series. But Aronica had been a huge Star Wars fan from when he first saw the movie in 1977.

Thinking about Star Wars, he realized that he could use some different tactics to tell some new stories in the universe: “It dawned on me that we could do things differently with Star Wars if Lucasfilm was willing to grant the license. The universe was so well developed and had such a great mythology, I believed ambitious novels could be created that honored the universe.”

In the fall of 1988, he put together a letter and sent it to Lucasfilm blindly: he had no idea if the company was even interested in publishing additional stories.

“I talked about wanting to publish these books as events, launching in hardcover, which was fairly unusual for licensed properties at that time.” Aronica recalled. “The core of my message was that we wanted to make the books as powerful to readers as the films had been to viewers.”

Aronica envisioned a line of tie-in novels that were more ambitious than other publishing programs. He wanted to tell stories that were greater in scale, and that actively advanced the story laid down by the films,rather than simply staging what he called “costume dramas”: stories utilizing all the trappings of their source material, “but offering very little more than what fans already had from the original source.”

He also outlined a plan that would set Bantam Spectra’s line of novels apart from what other tie-in franchises were doing: each book or set of books would be an event in and of itself: the new “novels [would be] great reading experiences, not just merchandise,” and would come out in hardcover, rather as mass market paperbacks. Most of all, they understood the books would have to continue a major legacy: “The core of my message was that we wanted to make the books as powerful to readers as the films had been to viewers. I made it very clear that we not only loved Star Wars, but that we wanted to treat it, in the book world, like a great literary property.”

Wilson was won over by Aronica’s pitch and granted a license to Bantam Spectra to produce a trilogy of novels. There were some stipulations: the first was that the books had to be well-written.

“I was trying to bring quality literature to a licensed fictional universe,” Wilson recalled. She also wanted to do something different from the typical tie-in novel. With the Star Trek novels as their main competition, Wilson knew she needed to differentiate her books. “[Star Trek was] constantly rebooting their program with new storylines. I didn’t want our plan to be like theirs, and one big difference was to make ours have one over-arching internal consistency.” Additional stipulations were that the stories had to take place after Return of the Jedi, none of the characters who were featured in the films could be killed off, and characters already dead could not be resurrected.

With the rights in hand, Aronica turned to his publishing team, who, after their initial excitement, began to take the next step: selecting an author to start off the program. “We looked at our existing authors first, then started throwing out other names who might be wooed to Bantam on the strength on the Star Wars project.” said Betsy Mitchell, Bantam Spectra’s senior editor. Bantam Spectra had a strong stable of authors: Margaret Weis and Tracy Hickman, David Brin, Dan Simmons, William Gibson, and others.

It was Mitchell who recommended Timothy Zahn: she had begun to work for Bantam Spectra a few years earlier, and had signed the science fiction author to a three-book deal for the publisher.

In 1977, Zahn was a graduate student studying physics when he first saw Star Wars. He was hooked. He had also begun writing on the side while studying: “I was working on a mathematical project that really wasn’t going anywhere. My advisor was too stubborn to give up. And he was out of town a lot, so it gave me a fair amount of time while I was stuck waiting for him to get back into town with not much to do, so I started writing as kind of a hobby,” Zahn told TheForce.net in 2000. When his advisor died of a heart attack, Zahn decided that he was more interested in pursuing writing than a doctorate, and left school.

Over the next couple of years, he published a number of stories in magazines such asAnalog Science Fiction and Fact, Amazing Stories, The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, and Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine, before he published his first novel,The Blackcollar, in 1983. The same year, he published Cascade Point in Analog, which earned him a prestigious Hugo Award for Best Short Story (the same year Return of the Jedi earned the Best Dramatic Presentation award.)

Mitchell had worked with Zahn at Analog, where she was the managing editor, and again at a newer science fiction publisher, Baen Books, where Zahn published a number of novels.

Star Wars Thrawn Trilogy #1: Heir to the Empire

Mitchell and her team sent Zahn’s name, along with several other names, to Wilson. “I picked Timothy Zahn from her selection,” Wilson said, “as Tim’s original novels read the closest to Star Wars to me.” At the same time, Mitchell brought over Sue Rostini as an assistant and publishing editor: together, they would help to manage the larger Star Wars universe from Bantam Spectra’s end.

Lucasfilm approved of the choice as well, and in November 1989, Zahn received the call: he would be writing in the universe he really loved, a prospect he found daunting. He had two guidelines: the novel had to take place after Return of the Jedi, and he couldn’t resurrect dead characters. Other than that, he had free reign. He needed to pick up where Lucas had left off, but there were challenges: the films’ most iconic villain, Darth Vader, had been killed, and the Rebellion appeared victorious. Zahn decided to extrapolate: the heroes needed to face a formidable enemy who was rallying the Empire.

To that end, he created Grand Admiral Thrawn, a master tactician who had risen in the Imperial ranks, along with a proposed dark Jedi: an insane clone of Obi Wan Kenobi. Along the way, he introduced Talon Karrde and Mara Jade, a smuggler and former imperial agent, respectively, to join in on the adventures.

Zahn had already begun to create his own background material when supplemental materials arrived from West End Games.

Star Wars Thrawn Trilogy #1: Heir to the Empire: The 20th Anniversary Edition

“I was just a couple of weeks into Heir when I received a big box containing some of the sourcebooks that West End Games had created over the years for the Star Wars role-playing game.” Zahn recounted in the annotations of the 20th Anniversary edition of Heir to the Empire. “Along with the books came instructions from Lucasfilm that I was to coordinate Heir with the WEG Material. As usual, I groused a little about that. But once I actually started digging into the books I realized the WEG folks had put together a boatload of really awesome stuff, including lists of aliens, equipment, ground vehicles, and ship types.”

The building blocks that West End Games had already created allowed Zahn to focus less on developing the world and more on the story. Given that Star Wars was lauded for taking place in a “used universe,” the ability for authors to reuse common elements only added to the feeling that these stories fit within the world that George Lucas had established.

When LucasFilm and Bantam Spectra finally signed off on their deal, Zahn was ready, and wrote his book in six months. His original title, Wildcard, was nixed by Aronica, who suggested Heir to the Empire instead. During the editorial stages, some of what Zahn had come up with had to be changed: the insane clone of Obi Wan Kenobi was replaced by Joruus C’baoth, a cloned Jedi Knight who had been tasked with guarding the Emperor’s repository. Lucasfilm was also protective of the Clone Wars and some other minor elements that Zahn had included, but after some edits, the company signed off on the book.

On May 1, 1991, Zahn’s Heir to the Empire arrived in bookstores, and the response was overwhelmingly positive. Aronica remembers “Lucasfilm’s offices were flooded with media queries asking if Heir was going to be the fourth movie.” Booksellers reported selling the book directly out of boxes, before they could even be shelved.

Heir to the Empire landed on the New York Times bestseller at number 11, and over the next couple of weeks, rose to the top, aided by its artificially low price of $15. The book demonstrated there was an incredible appetite for more stories from in the Star Wars universe.

Star Wars Thrawn Trilogy #2: Dark Force Rising

Zahn didn’t have much time to deliver them: he was already hard at work on the next installment of the trilogy, Dark Force Rising, due out the following year. A third installment, The Last Command, was set to arrive in 1993.

Lucasfilm was also interested in expanding their publishing program beyond adult novels. In 1992, they launched a young readers series under Bantam’s children’s imprint called the Jedi Prince series. Written by Paul and Hollace Davids, the series included The Glove of Darth Vader, The Lost City of the Jedi, Zorba the Hutt’s Revenge, Mission from Mount Yoda, Queen of the Empire and Prophets of the Dark Side, all of which arrived in bookstores between 1992 and 1993, capturing the imaginations of readers too young to have seen the films in theaters. While the books sold well over the years, they didn’t quite fit into the continuity of the adult books, and often had their events “retconed” to fit within the larger timeline.

Bantam Spectra found that they were sitting on top of a gold mine, and quickly contracted an additional twelve novels in the franchise. As the program expanded, Bantam Spectra had to contend with Lucasfilm’s stringent eye for quality. “There were a few, very rare times when we had to disapprove completed novels for failing on one or [level or another],” Wilson recalled, “but generally by having the right editorial team and great writers, this was not an issue.”

Star Wars Thrawn Trilogy #3: The Last Command

In early 2015, the fan site Star Wars Timeline published the entire text of a lost Star Wars novel authored by Kenneth C. Flint, The Heart of the Jedi was originally set to be published in 1993, after The Last Command, but was cancelled after being completed.

According to Flint, following the successes of Zahn’s novels, he was approached to write a book that took place immediately after Return of the Jedi. He completed and submitted it in 1992, but received little word about its status from his editors. “Finally, growing concerned, I contacted an agent, who contacted Spectra. He discovered only then that Spectra had determined my book couldn’t be published because it ‘no longer fit into the sequence for the new series.’”

Around the same time, another novel, Legacy of Doom, authored by Margaret Weisman, which would take place after it Heart of the Jedi, was also cancelled. Even if books reached the proposal stage, passed their outlines, and were written, there was always a possibility they still wouldn’t work.

According to Wilson, Lucasfilm had two main criteria. “My overriding concern was to publish great books. [They] also needed to feel like they fit into the Star Wars universe George Lucas had created in the movies.” The episode with Flint’s novel reveals the lengths they would go to assure the books satisfied expectations.

To fill the gap left by the cancellations, Bantam Spectra brought in another author: Kathy Tyers. Tyers had written a handful of science fiction novels for the publisher. She was ecstatic when she received a call from her then-editor Janna Silverstein, who asked if she would like to be a Star Wars author. “As I recall,” Tyers said, “there was about a two-second pause before I said ‘Yes!’”

She was assigned the post-Return of the Jedi slot. Tyers went to work; armed with a box of reference materials from West End Games, a VHS player, and the final film, she set about taking notes. She was to make sure that she didn’t contradict anything in Zahn’s trilogy, but was to advance the characters forward somehow. “At this point in the project, we were just starting to realize how valuable it would be to Star Wars fans if we created a storyline that moved the characters forward in time,” Wilson said. “We contrasted that plan with other SF spin-off series that were episodic in nature, each book leaving the characters exactly as they were when the book began.”

Star Wars The Truce at Bakura

Tyers came up with several concepts which she pitched to her editors at Bantam Spectra, who selected the idea that would eventually become The Truce At Bakura, which hit bookstores in January of 1994.

Tyers appreciated working within an established universe: “In a way, having the characters, situations, and environments already established made it like ‘real life.’ I had limited freedom to move the characters on the stage—but it was a really big stage.”

After her book, she kept up with the story, appreciating what the world was evolving into: “Many of [the novels] resonated beautifully with my sense of Star Wars, and what it was all about. Other authors had slightly different ideas. The richness of the universe created space enough (pun intended) for everyone to play.”

While Zahn and Tyers plugged away at their own books, Bantam Spectra looked for additional authors. They turned to Kevin J. Anderson, a young writer who had been publishing short fiction since 1982. His first novel,Resurrection, Inc., appeared in 1988, and was followed by several others. “I got a phone call out of the blue asking if I would like to write three sequels to one of my favorite movies of all time,” he recalled. “How could I turn down such a cool project like that?”

He set to work. Like Zahn and Tyers, he received West End Game’s reference books, as well as a copy of Heir to the Empire, the only book out at that time. “I got a pre-release review copy of Dark Force Rising, and Tim sent me the manuscript of The Last Commandas soon as it was finished.” The two authors spoke to make sure that they were avoiding one another’s stories. “We talked on the phone about where his story was going, and I set up my own.”

From the outset, Anderson knew that he was writing part of a larger story. He decided his trilogy would have two overarching narratives: one about Luke Skywalker rebuilding the Jedi Order, and the other about a secret Imperial installation called The Maw, where the Empire carried out the research that had eventually produced the Death Star.

Star Wars Jedi Academy Trilogy: Jedi Search / Dark Apprentice / Champions of the Force

Unlike Zahn’s trilogy, whose titles were released over three years, Anderson’s Jedi Academy trilogy, Jedi Search, Dark Apprentice, and Champions of the Force, would all hit stores in 1994. He wrote the trilogy all at once and turned in his drafts to Bantam Spectra and Del Rey for their approval. “By the time Betsy [Mitchell] left Bantam and I inherited her list,” Bantam Spectra editor Tom Dupree said on his blog, “she and Lou had mapped out the first wave of the new Star Wars cycle. I came aboard for the second book of our first paperback-original trilogy, Dark Apprentice by Kevin J. Anderson, and I worked on the Star Wars property for about five years thereafter.”

Anderson built on Zahn’s Thrawn trilogy in several ways: Han and Leia Solo continued to raise their twin children, Jacen and Jaina, while running the New Republic, and Luke Skywalker began to seek out new potential Jedi, gathering them at a training facility at the Yavin IV base from the first film. These plans are threatened as a new group takes control of the remains of the Empire and one of Skywalker’s novice apprentices falls to the Dark Side of the force.

Star Wars The Courtship of Princess Leia

Other books joined the growing storyline. The Courtship of Princess Leia, written by David Wolverton, told the story of how Han Solo and Leia Organa married. Vonda McIntyre’s The Crystal Star followed, with a plot on the part of a cultist to rebuild the Empire.

Wolverton came onboard in 1994 and completed his book in the spring. His approach was a little different: Zahn had established that Han and Leia were married, and his initial thought was “Oh, it couldn’t be that easy, not with their fiery personalities.” He wanted to see how they came together: “I have to admit that I wondered about Han’s character. Before he met Leia, he was a drug smuggler, and that suggested to me that he had a darker side. He was essentially an anti-hero, someone who had given up on life, on society.” He felt that when put under pressure, people revert back to older habits, which would complicate relationships.

In the novel, Han essentially kidnaps Leia and takes her to a planet that he’s won in a card game—a planet in Imperial territory. The plotline has come under criticism lately: “I have to admit, my wife and I had watched the old romance Seven Brides for Seven Brothers at about that time, with its wacky idea of having the male protagonists kidnap the brides, and I suspect that in the back of my mind, I was wondering, ‘Could you make a similar plot work in science fiction?’” He reflected on the issue: “Personally, I’m not a fan of the idea of drugging and kidnapping women. Or men. Or children, or dogs. But it did lead me to wonder about things like, ‘Could Leia ever forgive him for that? Could Han forgive himself?’ ‘What could bring them back together?’ Ultimately, I was interested in the idea that love is based upon two people’s past history, that it is something that builds and grows.”

Regardless of controversy, the novel was an immediate success: at one point, friends mentioned to Wolverton that they’d seen his book in a nearby bookstore; when he went to check it out minutes later, he found that they had completely sold out.

The book shot to the top of the New York Times bestseller list, outselling the second-place book by a 2-1 margin. “In fact, it was so popular that Bantam’s huge romance author called my editor to complain.” Wolverton said. “She yelled at my editor ‘Who in the hell is this Princess Leia!?’ Apparently she thought that I was taking her spot as Bantam’s lead author.”

The Star Wars Expanded Universe was off to a strong start, with each novel selling exceptionally well. Even as Bantam Spectra was operating without a roadmap, their approach seemed like the right one: engage established science fiction authors, partner with Lucasfilm, and build the story of Luke Skywalker, Han Solo, and Leia Organa. With only a handful of books in the works, it was easy for authors to coordinate and maintain continuity.

As the universe grew, however, new challenges would begin to emerge…

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

MOMENT OF TRIUMPH

Building a Galaxy Far, Far Away: New Stories (1995-1998)

by Andrew Liptak/

December 16, 2015 at 4:00 pm

Following the successes of Timothy Zahn’s Star Wars trilogy, Bantam Spectra found it had stumbled on a gold mine: the public had a ravenous appetite for new stories in the franchise, and over the first four years of the program, a timeline was slowly being written, under the careful watch of the publisher and their partners at Lucasfilm, chronicling the further adventures of Luke Skywalker, Leia Organa and Han Solo.

As each major entry was added, a larger picture of the post-Return of the Jedi story began to appear: an epic struggle between the New Republic and the Empire for control of the galaxy, told through the eyes of Luke Skywalker’s growing Jedi Order and the Solo family. As the books continued, the stories were beginning to grow more complicated.

Star Wars Tales from the Mos Eisley Cantina

In these still early years, Bantam Spectra editor Betsy Mitchell reached out to author Barbara Hambly, who had placed a short story in Kevin J. Anderson’s Tales of Mos Eisley Cantina. Mitchell had a new direction that she wanted to explore: a love interest for Luke Skywalker. Hambly accepted the project—“I didn’t need much convincing–I was an unshakeable Star Wars fan from the moment I first saw it”—and began Children of the Jedi, which would take place several months after Kevin J. Anderson’s Jedi Academy Trilogy. In it, Skywalker comes across an abandoned ship in the depths of space with the spirit of a long-dead Jedi Knight, Callista Masana, aboard.

“I have always loved haunted house stories, so I did [it] as a haunted house book,” Hambly said. “While I was growing up in the 1950s and ‘60s, people were still finding little nests of isolated Japanese soldiers on Pacific islands, stationed there in World War Two, who weren’t aware that the war was long over (I think the last poor fellow they found in 1985!), which I think turned my mind towards the thought of people—and computers—who are still fighting a war that’s been over for years, simply because nobody has told them to stop.”

Mitchell noted that the stories that Bantam Spectra had begun to put together were large and complicated, and as a result, the company opted to simply expand upon them: “Some stories just work better at a greater length. So rather than keep the writer working for a year or more on one long book, we decided to bring them out in duology or trilogy form. ”

Star Wars The Corellian Trilogy #1: Ambush at Corellia

One early example of this was Roger MacBride Allen’s Corellian trilogy, which delved a bit into Han Solo’s past, as well as events taking place long after Return of the Jedi. The trilogy was released in 1995, and was comprised of Ambush At Corellia, Assault at Selonia, andShowdown at Centerpoint. The longer trilogy was the furthest book out in the chronology, and considered not only Han Solo’s past, but also the lives of his children.

As Anderson’s books were hitting bookshelves in 1994, the administration behind the project was changing: Mitchell had left Bantam Spectra for a new position at Warner Books, replaced by Tom Dupree and Janna Silverstein.

Mitchell was incredibly important to the formation of the Star Wars line: she championed Timothy Zahn to write the first trilogy, and her personal tastes informed her acquisition decisions: “I was the one signing up novels, and that was a story I wanted to read,” she said. With new visionaries in place, the types of stories being commissioned began to change.

Star Wars Children of the Jedi

While Callista was set up to become Luke Skywalker’s love interest, other changes were put into place: fans had taken a liking to a character introduced in Zahn’s novels, Mara Jade, and the decision was made to eventually link the pair up. Hambly and Anderson shifted their plans. Bantam recommended simply killing off Callista, but both Anderson and Hambly disagreed. They felt that that wouldn’t be as emotionally powerful, so they changed the trilogy soDarksaber would be used to take Callista out of the picture, sending her on a quest to rediscover the Force.Children of Jedi appeared in bookstores in 1995, withDarksaber arriving shortly thereafter. Planet of Twilight wrapped up the arc in 1997.

In her novels, Hambly worked to introduce some new material into the Star Wars universe: Callista’s narrative drew its influences from cyberpunk, while she also looked “to address the culture of that world—the Imperial ‘high culture’ and the cultures of the individual planets—as cultures. As if this were a Jane Austen novel instead of Star Wars.”

Star Wars Darksaber

At the same time, Anderson and his wife Rebecca Moesta were hard at work on a new series aimed at younger readers, The Young Jedi Knights, while Moesta and Nancy Richardson worked on another youth-aimed series: Junior Jedi Knights. Each series would follow some of the newer, younger characters, such as Jaina and Jacen Solo. While aimed for a younger audience, “the stories and the writing were pretty much at the same level as my adult novels,” Anderson said. Unlike the earlier young adult novels, these were designed to fit better into the existing continuity.

More complicated projects were on the way. Following with Mitchell’s assertion that the stories that Bantam was working to tell were more complicated than a single installment, Bantam began to explore some new projects that went beyond a single author pitching their story for the franchise.

The first came in 1994, shortly after LucasArts released a flight simulator called X-Wing. It was enormously successful game for the growing home PC market, and Bantam began to explore the feasibility of releasing a line of novels that would build on that particular franchise.

Star Wars X-Wing #1: Rogue Squadron

Bantam Spectra approached Michael A. Stackpole, an author who had written military-style books in worlds such as Battletech, and who had worked with games in the 1980s, and asked him to write an initial four-book arc. After accepting, Stackpole made the trip to Skywalker Ranch, where he met with Lucy Wilson and Sue Rostoni to break the story. At the same time, Dark Horse Comics was also interested, and brought on Stackpole to help coordinate their stories, so that they would remain consistent.

The first comics came in 1995, taking place immediately after Return of the Jedi. With those released, Stackpole turned to the novels, pulling in some characters from the comics and bringing a cast of new ones. This was something different: rather than focusing on the core trio of Han, Luke, and Leia, the series highlighted background characters such as Wedge Antilles and Admiral Ackbar.

With the initial arc set before Zahn’s trilogy, Stackpole realized that with the military-style stories he was writing, he was in an ideal place to show off how the New Republic began to take over the Empire’s territory.

X-Wing: Rogue Squadron hit stores in 1996, and was followed that year by Wedge’s Gambit and The Krytos Trap. Stackpole’s final book in the arc, The Bacta War, arrived in 1997. Upon their publication, each became a New York Times bestseller, something that surprised everyone—expectations had been lowered because the books featured a different cast.

Given the success, Bantam wanted additional books, but Stackpole urged the publisher to bring on another writer: Aaron Allston. Allston, who had also worked in the gaming industry, was to write three additional novels. His books followed a new unit: Wraith Squadron, and his stories took on a different, more humorous track. Wraith Squadronappeared in March 1998, Iron Fist in July 1998 and Solo Command in February 1999. Stackpole returned the same year with Isard’s Revenge, while Allston completed another installment, Starfighters of Adumar.

Star Wars X-Wing #9: Starfighters of Adumar

The X-Wing series demonstrated an important thing to Bantam: up to that point, each of the Star Wars books had largely remained with the central cast of characters seen in the movies. The successes of the series helped to demonstrate that they weren’t essential to the success of other books, and helped to push the boundaries of the Expanded Universe by introducing other new characters that readers would follow. Indeed, a few years later, Stackpole wrote I, Jedi, which followed his lead character, Corran Horn.

Bantam Spectra had another complicated stories to map out. By 1993, Lucasfilm had made a decision: they would begin to work on a new trilogy of movies, while also re-releasing the original three films for A New Hope’s 20th anniversary. The next big project that would serve as a marketing and merchandising test of Lucasfilm’s franchisees: Shadows of the Empire.

Dupree had worked with author Steven Perry for another project, a novelization for the movie The Mask. Years later, Dupree asked Perry if he’d be interested writing for a much larger franchise. “I jumped on it,” Perry recounted. “A chance to put some of my favorite movie characters through their paces? Couldn’t pass that by.”

Star Wars Shadows of the Empire

The project would involve more than the typical parties: representatives from Dark Horse Comics, LucasArts and Bantam Spectra, and Kenner and Lewis Galoob Toys came together for a central meeting to figure out how to put together a collaborative story. Perry said he “was given to understand that since it had been a while, they were gearing up for the new movies, and wanted to do a kind of test run. [Shadows of the Empire] had everything except the movie, and they wanted to see how the parts would mesh.” The dry-run would test out how well each group could collaborate when the real merchandising push came.

At the meeting, Perry came up with several character concepts, while “each of the licensees offered up what they wanted or needed—Dark Horse wanted to feature Boba Fett, the game guys wanted a motorcycle chase, the toy folks had ideas of what characters they wanted to feature.” He jotted everything down and began work on a detailed outline that incorporated all of the ideas.

The outline grew to become a story bible, which in turn informed the creation of the novel and the ancillary parts that accompanied it. Perry spent four months writing the novel before turning it in to his editors. As he did so, he spoke a with his counterparts at Dark Horse to make sure that they had their stories straight, and consulted with some of the franchise’s prior authors for advice.

Perry was excited for the project because of the ability to explain a couple of untold periods in Star Wars lore—the story was set between The Empire Strikes Back andReturn of the Jedi, and served to set up the final film.

In 1996, the project rolled out. In April, Varese Sarabande released a soundtrack composed by Joel McNeely. Dark Horse put out the issues of their tie-in comic series between May and October. Perry’s novel appeared in May, while the video game arrived in stores on December 3.

The project was a success, and between Shadows of the Empire and the X-Wing series, the Expanded Universe was becoming more complex. Not only were authors working to conform to stories published as books, they were beginning to coordinate between comic books and video games to maintain a consistent storyline.

By this point, Lucasfilm made a change in a long-standing policy: they wanted to tell the early story of Han Solo. It’s a move that made a certain amount of sense, considering the original trilogy was set to be re-released to theaters. Dupree approached author A.C. Crispin to pen the trilogy.

Han Solo was Crispin’s favorite character, and she began to work on the project, with some stipulations. Han Solo’s parents were off limits—he couldn’t know who they were. Darth Vader and Emperor Palpatine couldn’t appear, and Han’s first encounter with Chewbacca, and the story of how he freed him from slavery, was also off the table.

Star Wars The Han Solo Trilogy #1: The Paradise Snare

Crispin also had to work around stories that had already been established in the 1980s by Brian Daley and L. Neil Smith. In her first book, The Paradise Snare,Crispin played out an origin story of a younger Han Solo, before jumping ahead several years to The Hutt Gambit, which worked around the older materials. The final installment, Rebel Dawn, helped to lead up to the events of A New Hope.

Kristine Kathryn Rusch joined the growing ranks of Star Wars authors when she published The New Rebellion in 1996. She noted that it was intimidating to enter an established and growing world: “I was a fan, and I knew how harsh the fans could be about things that didn’t fit in.”

With a body of work that preceded her entry, Rusch had the advantage of seeing what worked and what didn’t in earlier novels. “I took all the elements I loved about the movies and figured out what made them work,” she recalled. “Then I figured out which of the previous books I liked as well, and figured out what made them work.” She wrote the novel in late 1994, and coordinated with Lucasfilm to ensure it fit with the established canon.

Following The New Rebellion, Rusch met with Kevin J. Anderson and Lucasfilm officials to discuss the creation of a new series, only to have those plans thrown into disarray. Around this time, Bantam Spectra began to revisit how it paid authors: they had recently changed their license agreements with Lucasfilm, which raised the amounts that Bantam Spectra owed the company. With the sales volume declining, the publisher decided to change the arrangement from a traditional royalty model, where authors earned an advance and money per copy sold, to one in which authors would receive a single, upfront payment.

The change was met by intense criticism from authors and the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America, known as SFWA.

On October 1, the organization’s president, Michael Capobianco, sent a letter to Bantam Spectra’s president, Irwyn Applebaum, stating, “If Bantam persists in its present course, we will inform our membership and all interested parties that these contracts do not meet professional standards. We will also be obliged to oppose the flat fee scheme by negative publicity and direct appeals to Lucasfilm.” He sent an additional protest to Lucasfilm, blaming their contract negotiations for the new pay structure.

Lucasfilm, however, wasn’t behind the shift in pay, according to Lucy Wilson: “The novel authors were paid by the publisher, not by Lucasfilm. When their payment structure changed, that was Bantam’s decision.”

The reaction among the pool of Star Wars authors was mixed. Some denounced the publisher and refused to work under the new contract; others opted to continue to write for the franchise. Rusch was caught in the middle: according to her, her name was affixed to the letter, despite the fact that she wasn’t a member of the organization. The series that she was working on with Anderson ended up being cancelled, and Rusch was never invited back. “I haven’t been able to work with Lucasfilm again—through no fault of my own. To say that I’m disappointed is an understatement.”

Kevin J. Anderson and Rebecca Moesta noted that they would finish out their contractual obligations with Bantam Spectra, but wouldn’t write more books for the company: “Both my wife and I will not be writing any more SW novels under the Flat Fee Contracts; however we will continue to write the paperback Young and Junior Jedi series.”

Steve Perry, who wrote Shadows of the Empire, did not sign the letter, and didn’t think that what Bantam Spectra was offering was a bad deal: “I had gotten the royalty and a small advance on [Shadows of the Empire], and I liked that. I made more in the long run, but the flat-fee was a goodly sum, and it would have taken some time to get past that much to a royalty.” Still, he had concerns: “…there is a worry that such a deal will set a precedent and that shared universe work will all become flat fee. ”

A.C. Crispin, who had just finished her first trilogy, also slammed the deal: “The problem here as I see it is that it’s just a done deal; it’s a flat offer, no negotiation. Personally, I’d rather stake my abilities as a writer who cares about her work. Who puts a lot of time, effort, and research into producing the very best tie in book I can, and get a negotiated contract for a small advance and royalty so I would not feel ‘just like a hired hand.’ I want a stake in how well my books sell. ”

This wasn’t a universal feeling, though: Michael A. Stackpole noted that he was sticking with the publisher and franchise: “Above and beyond the money stuff, I’m writing these books because I want to write them. I’ve got more than enough work in my own universes to work on, but I like the Star Wars universe, love the characters I’ve created, and I want to finish off their stories”

Stackpole noted that his final X-Wing novel, Isard’s Revenge, and his hardcover standalone, I, Jedi, were written under the new contract terms, saying that because his older X-Wing novels still received royalties, the new books he sold would likely translate into ancillary earnings from the increased sales of earlier books.

By the end of the 1990s, Bantam Spectra commissioned Timothy Zahn to write another novel, one that would roughly close out their era of stories. In it, the Empire would do something unthinkable: it would come to peace terms with the New Republic, bringing the galactic civil war to an end. As this happens, forces collude to interfere, while Zahn’s long-lost villain Thrawn is rumored to have returned, decades after his death.

Star Wars The Hand of Thrawn #1: Specter of the Past

Zahn’s story was originally slated to be a single novel, but expanded into two: Specter of the Past and Visions of the Future. In many ways, Zahn’s Thrawn duology was the last hurrah of the Bantam Spectra publishing era, closing out the adventures with the author and story that had started it all.

Looking back, the Bantam Spectra books helped to define the Expanded Universes: the further adventures of not only the central heroes of the saga, but the entire galaxy. The appeal of Star Wars has always been, in part, the trappings of the universe, in addition to Luke Skywalker, Leia Organa, and Han Solo.

It’s clear the books’ success was firmly rooted in the attitudes of Lucasfilm and the individual authors, who strove to match the stories from the films, extrapolating forward. But as the Expanded Universe grew, it became clear that fans were involved in the bigger picture: what was the fate of the Rebellion and the Empire, and how did the heroes remain involved? Furthermore, who else was involved in the story? Through Mara Jade and Corran Horn, fans found new characters to root for, bringing them to levels almost on par with that of their movie counterparts.

By the end of the 1990s, however, there was a creeping sense of exhaustion within the franchise, both from Bantam Spectra and Lucasfilm: the novels weren’t selling as well, and they had begun to feel repetitive, featuring a “superweapon of the week” formula. That’s not to discount the phenomenal work that went into the Expanded Universe: Bantam Spectra did some interesting things with their novels, collaborating with fellow licensees like Dark Horse Comics and West End Games to ensure that they were producing a consistent continuity, while also working on multiple-author cycles, such as the Callista trilogy and the X-Wing series. Moreover, the continuity was the product of a collaborative effort between many authors, producing an epic story that grew as it was told.

Above all, Bantam Spectra arguably saved the franchise. Without the massive success of Timothy Zahn’s Heir to the Empire and its followup novels, Star Wars may very well have continued to dwindle, becoming just another fondly remembered film. The books demonstrated there was a strong appetite for new stories, and while probably not the lynchpin to Lucas’ decision to begin work on the prequels, it certainly didn’t hurt. What the Expanded Universe most certainly did was to create and foster a vibrant fan base that remained engaged with, and loyal to, the once-dormant franchise.

And even as Bantam Spectra’s time in the galaxy far, far away was coming to an end, Lucasfilm had greater plans for the Expanded Universe…

Building a Galaxy Far, Far Away: The Story of the Star Wars Expanded Universe, Episode I

by Andrew Liptak/

December 14, 2015 at 12:30 pm

It was the moment that readers were dreading since news broke that George Lucas had sold Lucasfilm to Disney for $4 billion: the moment the Star Wars canon would be stripped down and rebuilt from scratch. The Expanded Universe that had sprung up from the ashes of the second Death Star was not going to lead to Star Wars: The Force Awakens.

After the theatrical release of Return of the Jedi, a larger story had emerged, revealing what happened to the Rebels and the remnant of the Empire in the wake of that “final” film. It grew through a myriad of comic books, novels, roleplaying and video games, and other tie-ins, arcing backward and forward in time, collectively becoming known as the Star Wars Expanded Universe.

The Star Wars Trilogy: A New Hope/The Empire Strikes Back/Return of the Jedi

On April 25, 2014, Lucasfilm and Disney announced the creation of a new “Story Group” responsible for maintaining and developing the overarching story of the franchise. The announcement meant that the Expanded Universe that had been building since the early 1990s would no longer be considered canonical, and that the upcoming films would rely on a new, coordinated mythos. The time between Return of the Jedi and The Force Awakens would be reconstructed with a new series of books, comics and games, and while the older Expanded Universe novels would continue to be published, they would exist under a new designation, “Star Wars Legends.”

Fans immersed in the Expanded Universe were disappointed: the characters and adventures that they had followed for so long were going to end. Others were more optimistic—the Expanded Universe had grown organically over almost two decades; there were entries reviled by readers, numerous dead ends, and stories that were at times contradictory or difficult to reconcile. Maybe a fresh start would produce a canon that would be easier to manage.

For some, the Expanded Universe provided the definitive post-Return of the Jedi story, continuing the adventures of Han Solo, Leia Organa, and Luke Skywalker and giving a spotlight to some of the movie’s lesser known players like Admiral Ackbar and Wedge Antilles, and introducing numerous new characters such as Callista, Mara Jade, Grand Admiral Thrawn, Corran Horn, and Dash Rendar, some of whom became as popular with readers as their film counterparts.

How did these stories pick up the Star Wars mantle and become such a phenomenon in their own right, and how did the Expanded Universe take shape—and change over the course of its life? The answer lies in the numerous authors and editors who were tasked with continuing George Lucas’s grand story into the unknown.

Star Wars Splinter of the Mind's Eye

Every saga has a beginning…

Star Wars had always been closely linked to novels. Star Wars: From the Adventures of Luke Skywalker appeared in bookstores in November 1976, marking the film franchise’s entry into the public consciousness. The novel was ghostwritten by Alan Dean Foster, who had been brought in by Ballantine Books as an experienced tie-in writer, and who drew from the scripts and concept art of the original film.

Following the success of the movie, Ballantine Books released what had been planned as a contingency: a story written up by Foster to become the basis for a sequel, should Star Wars prove to be only a moderate success. Instead, of course, Star Wars was a massive success, and Del Rey simply released Splinter of the Mind’s Eye in 1978 as a further adventure in the franchise. It became an immediate bestseller. “The world was hungry for any new Star Wars story,” wrote Chris Taylor in How Star Wars Conquered The Universe. “Children would reread the paperback until it fell apart in their hands.”

Splinter of the Mind’s Eye became the first inkling of further adventures in the franchise, and it was closely followed by several other novels from Brian Daley: Han Solo at Star’s End and Han Solo’s Revenge, each released in 1979, and Han Solo and the Lost Legacy, which followed in 1980. The Empire Strikes Back screenwriter Leigh Brackett had signed on to write a novel about Princess Leia, but shortly after completing her screenplay, cancer took her life, and that novel was never written. These tie-in novels showed that Star Wars wasn’t limited to the adventures, characters, and stories of the film: they provided the first glimmers of a larger world beyond what was onscreen, an exciting “expanded universe” in which the stories of the film’s central characters lived on after the credits stopped rolling.

Three more books followed in 1983, following another hero from The Empire Strikes Back and written by L. Neil Smith: Lando Calrissian and the Mindharp of Sharu. Lando Calrissian and the Flamewind of Oseon and Lando Calrissian and the Starcave of ThonBoka. Other adventures appeared in a line of comic books from Marvel.

While these entries added to the Star Wars saga, the books and overarching story that we now know as the Expanded Universe truly have their roots in a small gaming company called West End Games. Founded in 1974 by Daniel Scott Palter, the company initially produced board games, before shifting to produce roleplaying games in 1984.

Bill Slavicsek joined the company in 1986 after answering a blind ad in The New York Times. He was brought on as a games editor, and branched into game design and development before the end of his first year.

Slavicsek had been a longtime science fiction fan and gamer. He read everything he could get his hands on, and when Star Wars hit theaters in 1977, he returned to the theater 38 times.

The same year he joined West End Games, the company worked to secure a license for the franchise. They had already worked with some high-profile properties: Star Trekand Ghostbusters, which ultimately won over officials at Lucasfilm. “I can only guess,” Slavicsek reacalled, “but I think the company pursued the license because the films had such an impact on all of us and they thought it would be a perfect match with the kinds of products that WEG did at that time.”

The West End Games team began working on a roleplaying game sourcebook, started by Curtis Smith, the head of the creative team. When management duties pulled him away from the project, Slavicsek ended up writing most of the book, assigned to the project when the team learned that he was a big Star Wars fan.

His approach was simple: “…to create material that worked with the stuff we saw on the big screen. I saw it as my job to explain what hadn’t been explained and to fill in the blanks so that Gamemasters could run campaigns.”

Roleplaying games, by their very nature, required the production of volumes and volumes of additional material, according to author Troy Denning, who worked as a game designer and writer for companies such as TSR and West End Games. A novel, he noted, only required what was necessary for the story at hand. Roleplaying games, on the other hand, required massive amounts of extra information for gamemasters to use.

The West End Games team had to produce an extraordinary amount of material for their games to work. They went to the original films, novels, scripts, and artwork, and were granted access to Lucasfilm’s archives to mine for information.

Between 1987 and 1999, West End Games produced numerous sourcebooks—notably the Galaxy Guides—for use in the games. “I don’t think that it would be an exaggeration to say that there wouldn’t be an EU without West End Games,” Denning noted.

Star Wars The Han Solo Adventures

The Galaxy Guides and other supplements were authoritative books that provided an enormous amount of raw material for Star Wars fans. Elements such as the names of alien species and their histories, the names of planets, weapons, spaceships, histories, and more were created for use in the games. Denning noted that working on them was a Star Wars fan’s dream: “My assignment was to take all of the characters in the cantina scene and to write their backgrounds and histories of their species. Whatever their common names are now, I made those up. ”

Slavicsek also wanted an element of realism for the games. “I wanted to smooth out any of the rough edges and make the place feel real. For example, ‘Hammerhead’ might be a fine name for an alien on a piece of concept art, but as I explained to my contact at Lucasfilm, that wouldn’t work as an official species name. No species is going to call itself something that sound derogatory or silly. So, in the fiction, Imperials and other elitists will call them ‘Hammerheads,’ but they call themselves ‘Ithorians.’” This philosophy was critical in shaping the tone of the materials that they were putting together. Star Wars stunned audiences by presenting a massive world that felt lived-in; the materials that West End Games was creating followed the same line of thought, and helped provide the context for what was seen on the screen.

Star Wars The Lando Calrissian Adventures

While there had been additional stories told in the Star Wars universe, it was the West End Games materials that really demonstrated to Lucasfilm officials the value of expanding their horizons. “[Lucasfilm was] extremely excited by the prospect of us adding to the existing lore.” Slavicsek recalled. “The RPG book began that process by expanding on a few basic concepts, including the Force and hyperspace travel, but it was the Star Wars Sourcebook that really opened their eyes to the kinds of details we could fill in to help explain their universe.”

The gaming supplements were adding something interesting to the Star Wars universe: it was raw building blocks for storytellers—at the time, gamers—to create their own tales. The West End Games materials became akin to an operating system upon which all Star Wars tales would be based.

Lucasfilm kept a close eye on what they were producing, ensuring that their creations were in line with the tone and intentions of the films. Everything was looked over by the company, and even George Lucas weighed in. “They reviewed and approved everything.” Slavicsek explained. “I could even ask George Lucas a few select questions during the process, as long as I framed them as ‘yes or no’ questions so he could fire back a quick answer.” Lucasfilm had firm rules in place, and suggested alternatives or asked the game makers to steer clear of certain elements, such as Yoda’s species and whether or not Stormtroopers were clones.

West End Games’ Star Wars line was extremely popular, becoming a major source of profit for the gaming company. In the years following the release of Return of the Jedi, there was an appetite for new Star Wars content from the general public, bolstered by persistent rumors of plans for sequel and prequel trilogies.

Star Wars Thrawn Trilogy #1: Heir to the Empire: The 20th Anniversary Edition

Troy Denning asserted that without the efforts of West End Games, the Expanded Universe as we know it wouldn’t exist. “West End Games was huge in establishing the EU before there was an EU. I don’t think that it would be an exaggeration to say that there wouldn’t be an EU without West End Games. The sheer amount of material created for a roleplaying game helped to establish the foundation for the EU and the books that game later on.” He went on to note that after while he was reading Timothy Zahn’s novel Heir to the Empire, he noticed that some of the species that he had invented for Galaxy Guide 4 had been incorporated into the text, something that he was very excited to see.

By the late 1980s, West End Games had done something unique: they had established the elements from which any fan could work off of to tell their own stories in the universe with some level of consistency. The story of Star Wars had ended with Return of the Jedi, and there were no concrete plans for additional movies. Without the efforts of Slavicsek and his team at West End Games, the universe would have simply ended.

Despite West End Games work, by the late 1980s, Lucas Licensing had begun to spool down its efforts: there were no new films planned, and slowly, it seemed as though Star Wars would slip away, fondly remembered by fans who had seen it, and by an even smaller group of fans who played their own adventures, using building blocks that had been written down.

However, the seeds for something greater had been planted, and were waiting for the right encouragement to blossom. More on that tomorrow.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

BRAINS AND THRAWN

Building a Galaxy Far Far Away: Heir to the Films (1990-1994)

by Andrew Liptak/

December 15, 2015 at 4:00 pm

Between 1977 and 1983, George Lucas’s Star Wars franchise electrified a generation, changed cinema forever, and created a passionate fan base. But with no new films in sight by the end of the 1980s, Lucasfilm began to move on from its science fiction properties. The grand space epic might have ended with the handful of short stories and reference materials had it not been for Lou Aronica.

In 1986, Lucasfilm eased up on the licensing campaign: Return of the Jedi had been out of theaters for three years, and at the time, Lucas felt he was done with directing and done with the franchise that had made him so famous. With the movies receding into the past, there didn’t seem to be a market for the action figures, comics, video games, and other tie-ins that accompanied the trilogy. It was time to look to new creations.

Shadow Moon: First in the Chronicles of the Shadow War

In the 1987, Lucy Wilson, the finance director in Lucasfilm’s licensing department, was promoted to director of publishing , overseeing literary offerings involving the company’s intellectual property. By this point, she had worked on a trilogy of tie-in novels for Lucasfilm’s latest offering, Willow, which would come out years later as Shadow Moon, Shadow Dawn, and Shadow Star. The last Star Wars novel, Lando Calrissian and the Starcave of ThonBoka, had been published years earlier, and “no one at Lucasfilm was thinking of doing new Star Wars novels in 1989.”

Wilson was attending a book fair in New York, working on unrelated projects, when she met with publisher Byron Preiss. He wasn’t interested in her ongoing projects, but mentioned that they should start looking at Star Wars novels instead—those would likely sell.

“That seemed like a really good idea to me. Having been at Lucasfilm, since before the release of the first Star Wars movie,” Wilson recounted, “I knew the impact it had and felt there were a lot of people out there who were dying for something new in the universe.”

She returned home and proposed that the company license a couple of novels. With the blessing of George Lucas, she began to explore her options. Out of contractual obligations, she approached Ballantine Books first, but they passed: they didn’t believe that they would be successful with no new movies on the horizon. Wilson then went through the company’s correspondence from publishers, and came across a letter from Bantam Spectra publisher Lou Aronica, written a year earlier. She remembered that she had been impressed by the company’s presence and offerings at the book fair, and gave him a call.

Aronica joined Bantam Books in 1979 after completing college, and after several years, took over their science fiction line. During that time, he shepherded number of books and authors that established Bantam as a major publisher of genre fiction: David Brin, Gregory Benford, and William Gibson, as well as well-established authors such as Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke. In 1985, he launched a dedicated genre imprint called Bantam Spectra.

As a publisher, he hadn’t been all that interested in working with licensed properties, as he had largely been disappointed with the Star Trek novel series. But Aronica had been a huge Star Wars fan from when he first saw the movie in 1977.

Thinking about Star Wars, he realized that he could use some different tactics to tell some new stories in the universe: “It dawned on me that we could do things differently with Star Wars if Lucasfilm was willing to grant the license. The universe was so well developed and had such a great mythology, I believed ambitious novels could be created that honored the universe.”

In the fall of 1988, he put together a letter and sent it to Lucasfilm blindly: he had no idea if the company was even interested in publishing additional stories.

“I talked about wanting to publish these books as events, launching in hardcover, which was fairly unusual for licensed properties at that time.” Aronica recalled. “The core of my message was that we wanted to make the books as powerful to readers as the films had been to viewers.”

Aronica envisioned a line of tie-in novels that were more ambitious than other publishing programs. He wanted to tell stories that were greater in scale, and that actively advanced the story laid down by the films,rather than simply staging what he called “costume dramas”: stories utilizing all the trappings of their source material, “but offering very little more than what fans already had from the original source.”

He also outlined a plan that would set Bantam Spectra’s line of novels apart from what other tie-in franchises were doing: each book or set of books would be an event in and of itself: the new “novels [would be] great reading experiences, not just merchandise,” and would come out in hardcover, rather as mass market paperbacks. Most of all, they understood the books would have to continue a major legacy: “The core of my message was that we wanted to make the books as powerful to readers as the films had been to viewers. I made it very clear that we not only loved Star Wars, but that we wanted to treat it, in the book world, like a great literary property.”

Wilson was won over by Aronica’s pitch and granted a license to Bantam Spectra to produce a trilogy of novels. There were some stipulations: the first was that the books had to be well-written.

“I was trying to bring quality literature to a licensed fictional universe,” Wilson recalled. She also wanted to do something different from the typical tie-in novel. With the Star Trek novels as their main competition, Wilson knew she needed to differentiate her books. “[Star Trek was] constantly rebooting their program with new storylines. I didn’t want our plan to be like theirs, and one big difference was to make ours have one over-arching internal consistency.” Additional stipulations were that the stories had to take place after Return of the Jedi, none of the characters who were featured in the films could be killed off, and characters already dead could not be resurrected.

With the rights in hand, Aronica turned to his publishing team, who, after their initial excitement, began to take the next step: selecting an author to start off the program. “We looked at our existing authors first, then started throwing out other names who might be wooed to Bantam on the strength on the Star Wars project.” said Betsy Mitchell, Bantam Spectra’s senior editor. Bantam Spectra had a strong stable of authors: Margaret Weis and Tracy Hickman, David Brin, Dan Simmons, William Gibson, and others.

It was Mitchell who recommended Timothy Zahn: she had begun to work for Bantam Spectra a few years earlier, and had signed the science fiction author to a three-book deal for the publisher.

In 1977, Zahn was a graduate student studying physics when he first saw Star Wars. He was hooked. He had also begun writing on the side while studying: “I was working on a mathematical project that really wasn’t going anywhere. My advisor was too stubborn to give up. And he was out of town a lot, so it gave me a fair amount of time while I was stuck waiting for him to get back into town with not much to do, so I started writing as kind of a hobby,” Zahn told TheForce.net in 2000. When his advisor died of a heart attack, Zahn decided that he was more interested in pursuing writing than a doctorate, and left school.

Over the next couple of years, he published a number of stories in magazines such asAnalog Science Fiction and Fact, Amazing Stories, The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, and Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine, before he published his first novel,The Blackcollar, in 1983. The same year, he published Cascade Point in Analog, which earned him a prestigious Hugo Award for Best Short Story (the same year Return of the Jedi earned the Best Dramatic Presentation award.)

Mitchell had worked with Zahn at Analog, where she was the managing editor, and again at a newer science fiction publisher, Baen Books, where Zahn published a number of novels.

Star Wars Thrawn Trilogy #1: Heir to the Empire

Mitchell and her team sent Zahn’s name, along with several other names, to Wilson. “I picked Timothy Zahn from her selection,” Wilson said, “as Tim’s original novels read the closest to Star Wars to me.” At the same time, Mitchell brought over Sue Rostini as an assistant and publishing editor: together, they would help to manage the larger Star Wars universe from Bantam Spectra’s end.

Lucasfilm approved of the choice as well, and in November 1989, Zahn received the call: he would be writing in the universe he really loved, a prospect he found daunting. He had two guidelines: the novel had to take place after Return of the Jedi, and he couldn’t resurrect dead characters. Other than that, he had free reign. He needed to pick up where Lucas had left off, but there were challenges: the films’ most iconic villain, Darth Vader, had been killed, and the Rebellion appeared victorious. Zahn decided to extrapolate: the heroes needed to face a formidable enemy who was rallying the Empire.

To that end, he created Grand Admiral Thrawn, a master tactician who had risen in the Imperial ranks, along with a proposed dark Jedi: an insane clone of Obi Wan Kenobi. Along the way, he introduced Talon Karrde and Mara Jade, a smuggler and former imperial agent, respectively, to join in on the adventures.

Zahn had already begun to create his own background material when supplemental materials arrived from West End Games.

Star Wars Thrawn Trilogy #1: Heir to the Empire: The 20th Anniversary Edition

“I was just a couple of weeks into Heir when I received a big box containing some of the sourcebooks that West End Games had created over the years for the Star Wars role-playing game.” Zahn recounted in the annotations of the 20th Anniversary edition of Heir to the Empire. “Along with the books came instructions from Lucasfilm that I was to coordinate Heir with the WEG Material. As usual, I groused a little about that. But once I actually started digging into the books I realized the WEG folks had put together a boatload of really awesome stuff, including lists of aliens, equipment, ground vehicles, and ship types.”