69

rate or flag this page

By

watcher by night

Enjoy a very nice preview of Marjorie Burns' "Perilous Realms", which provides very original and thought-provoking insights into Tolkien's 'mythology'

Enjoy a very nice preview of Marjorie Burns' "Perilous Realms", which provides very original and thought-provoking insights into Tolkien's 'mythology'

- Read Marjorie Burns' "Spiders and Evil Red Eyes"

Preview almost all of Marjorie Burns' chapter, which explores fascinating and highly detailed connections between Tolkien's work and Norse and Celtic mythology. And yes, Ayesha makes an appearance as well. For more, see Amazon page's preview.

First, a look at Galadriel in the familiar Universe of LOTR and the Silmarillion

Galadriel is an important figure not only in The Lord of the Rings, but also in Tolkien's Silmarillion. The Silmarillion lays out a vast expanse of Middle Earth's history and mythology, of which the War of the Ring, as told in The Lord of the Rings, is only a very small part. If you have only read and/or seen The Lord of the Rings, then this article will include some small plot spoilage from the Silmarillion, but such spoilers will, I think, be more on the order of teasers to whet your appetite. Besides, with the Silmarillion being on the order of a broad historical work, it perhaps cannot properly be said to have a plot in the conventional sense.

Galadriel is an Elven Queen. We meet her in The Lord of the Rings, when the company of the fellowship of the Ring enters Lothlorien. It is interesting to compare and contrast the way in which Galadriel is presented in the book, with the way in which she is presented in Peter Jackson's movie. However, I will not dwell here on such similarities and differences at any great length, wishing merely to note a few points that may be relevant to the topic at hand.

Cate Blanchett's portrayal of Galadriel in the movie trilogy was very interesting. I may as well say, however, that I was disappointed in the omission from the movie of something Galadriel said to Gimli at their first meeting in the book. In the book, seeing that the Dwarf was sorrowful and bowed with grief, not only at the loss of Gandalf at the Bridge of Khazad-dum, but also at the loss of his friends and relatives in Moria, and in a sense, Moria itself, she says kind words to Gimli that not only comfort him, but also completely changes the way in which he sees Galadriel. Here, since it was omitted from the movie, I will take the liberty of quoting at length what Galadriel said.

"Do not repent of your welcome to the Dwarf," she begins, speaking at first to her husband, Celeborn. "If our folk had been exiled long and far from Lothlorien, who of the Galadhrim, even Celeborn the wise, would pass nigh and would not wish to look upon their ancient home, though it had become an abode of dragons?"

Then, continuing, Galadriel addressed the following directly to Gimli. "Dark is the water of Kheled-zaram, and cold are the springs of Kibil-nala, and fair were the many-pillared halls of Khazad-dum in Elder Days before the fall of mighty kings beneath the stone." Saying this, Galadriel smiled.

And then we are told of Gimli's change of heart and opening of eyes: "And the Dwarf, hearing the names given in his own ancient tongue, looked up and met her eyes; and it seemed to him that he looked suddenly into the heart of an enemy and saw there love and understanding. Wonder came into his face, and then he smiled in answer.

"He rose clumsily and bowed in dwarf-fashion, saying: 'Yet more fair is the living land of Lorien, and the Lady Galadriel is above all the jewels that lie beneath the earth!'"

This, for me, is an especially poignant and beautiful moment in the book, and one that also underscores Tolkien's gift, at least as a writer, for putting himself into someone else's shoes and seeing surprisingly deeply into both sides of an argument or conflict. In this case, the interchange between Galadriel and Gimli must be understood in terms of the history between the elves and the dwarves, who at certain times in the past had actually been at war with each other. Thus Gimli's surprise and wonder when someone he had expected to receive him with hostility instead not only welcomes him, but also expresses the keenest insight into his feelings and his culture, and apparently even thinks his ancestral home is as beautiful as Gimli himself does. It might also be in order to here recall that many elves thought of Moria with dread and distaste, because of the rumor of some ancient terror that haunted the place. This moment with Galadriel also marks a turning point in the way Legolas and Gimli view one another, and in a sense marks the genesis of what would become a close and lasting friendship between the prince from Mirkwood and the son of Gloin.

What else does the exchange with Gimli tells us about Galadriel? She is wise and insightful, and capable of great kindness. She looks for ways to heal wounds. She strives to give each member of the fellowship hope, even after the loss of their leader and the horrors of the ordeals through which they have already passed, and despite the dread of the unknown challenges that may await them if they continue their quest. She seems an immortal creature of light, angelic almost.

Yet, the strange, unsettling, ominous undertone present in the movie version, during Galadriel's first meeting with the company of the ring, can, I believe, be justified in some degree from the written texts. Her attempts to give each member of the Company hope seem strangely to have a double meaning: it would be possible, it seemed, to interpret her words as tests, almost as temptations. Now, Galadriel was a being whose life has actually spanned thousands of years of time in Middle Earth, and not just Middle Earth, but also in lands beyond the sea unknown to mortal man. I suppose it may seem a bit cliched to say that Galadriel is complex, and that she has a "dark side". But I for one find it anything but cliched to read The Lord of the Rings and the Silmarillion and contemplate the context in which Galadriel lives and ultimately makes her choice to return into the west, diminishing and fading-- at least as far as Middle Earth is concerned, and the kingdom over which she and Celeborn have ruled for many years.

Long ago in the past, many of the elves had been embroiled in an event which they referred to as the 'Kinslaying', which had been somewhat on the order of a civil war, with elf fighting against elf. The surviving elves looked upon the Kinslaying with grief and shame. Even Galadriel herself had apparently been compromised in some ways by this bitter event, although there were conflicting accounts of her degree of involvement, many of which seemed to indicate she had wished to avoid any bloodshed. Nevertheless, the time and the way in which Galadriel first came to Middle Earth were in some way intertwined with the events of and surrounding the Kinslaying. Thus there was a dark thread running through the course of Galadriel's coming to Middle Earth and the building of a place of security in Lothlorien, which seemed to indicate a dark thread running through her own nature.

The choice in the movie version of The Fellowship of the Ring to have Galadriel narrate the opening voiceover gains deeper resonance when Galadriel's past is kept in mind. "Men," she tells us, "...above all else desire power." This may sound as if elves merely look down on humans. But Galadriel also tells us in the voiceover that besides the nine rings "gifted to the race of men," "three [rings] were given to the Elves," and that furthermore, "within these rings was bound the strength and will to govern each race."

Now one of the things that is revealed to Frodo during his stay in Lorien is that Galadriel is actually, although secretly, the bearer of one of the three rings of power that had been given to the Elves. Without her ring of power, she would have been unable to make and maintain Lothlorien as a place of refuge and safety against Sauron's forces.

And what, in her voiceover, does Galadriel herself tell us about the ring of power that she holds and wields? Within it is "bound the strength and will to govern... [her] ...race." The plot thickens, if we consider that Galadriel's choice to come to Middle Earth in the manner she did after the Kinslaying was done against the wish of the Valar, who within the mythology/history of Middle Earth and the Undying Lands across the sea, could be understood as being (although only roughly) analagous to the Gods of Olympus in Greek mythology. So Galadriel's background of apparent wilfullness, or rebelliousness, may have perhaps been reinforced by the possession of a ring of power that had bound within it "the strength and will to govern." It would have appeared to her a tool which she could use to do much good in preserving and protecting that which was fair and good in Middle Earth. Yet, at the same time, it would be a tool strangely well matched to what I will term her darker or more ambivalent ambitions, ambitions which she apparently restrains, yet which we are able to glimpse or find hints of within LOTR and the Silmarillion.

Now, if we return again to that opening voiceover, the time is ripe to note that Galadriel also tells us that "they were all of them [meaning the elves, men and dwarves who had received rings of power] deceived. For another ring was made. In the land of Mordor, in the fires of Mount Doom, the Dark Lord Sauron forged in secret a Master Ring to control all others." Thus, even the ring held by Galadriel, though it might not be turned directly to any evil, at least while Galadriel held it, was still bound in some way to the Master Ring of Sauron.

Then, with the arrival of Frodo at Lothlorien, bearing the Master Ring itself, Galadriel finds herself at another one of those critical junctures that, I suppose, we all face along the paths we travel in life. Here is another tool, like and yet unlike the tool she accepted long ago and used to the benefit of many. The Master Ring is even more powerful than the ring of power which she already holds. She knows, however, that the Master Ring is so intimately intertwined with Sauron's "cruelty... malice, and... will to dominate all life," that any attempt to wield it will be twisted towards evil ends, no matter what the original intentions of the user.

Yet it is strangely tempting to think that perhaps the Master Ring can be "rehabilitated" and turned to serve good ends. We might ourselves reflect that when Bilbo himself first came into possession of the Ring, he was able to accomplish some good with it, such as saving thirteen dwarves from some very large and hungry spiders. And Galadriel was someone very different from the rather humble Bilbo; she was a being immortal, of great understanding and innate abilities, even without a ring of power. Surely, if anyone could wrest the One Ring not only from Sauron himself, but even from the very nature which Sauron had instilled within the Ring, it would be Galadriel herself? Against such plausible-sounding rationalizations, would an inner voice of warning be powerless? More especially so, because Galadriel was further burdened by a knowledge that if Sauron's One Ring was unmade, all of the other Rings of Power, since they were subtly but irrevocably bound to the One Ring, would also in a sense be unmade, and with the fading away of their power would pass away her ability to preserve and protect those things of Middle Earth so dear to the Elves.

This quandary adds many layers of depth, resonating back through ages of time, to Galadriel's eventual "temptation" by Frodo and her response to it. The temptation occurs after Frodo has looked into Galadriel's Mirror, and is an act apparently unpremeditated on Frodo's part and without guile. Yet the temptation is nonetheless very real, a 'sore temptation', as the saying goes. The temptation consists of Frodo offering freely to give to Galadriel the very thing which she both secretly desires and secretly dreads, the One Ring itself.

Hear what Galadriel then says. "And now at last it comes. You will give me the Ring freely! In place of the Dark Lord you will set up a Queen. And I shall not be dark, but beautiful and terrible as the Morning and the Night! Fair as the Sea and the Sun and the Snow upon the Mountain! Dreadful as the Storm and the Lightning! Stronger than the foundations of the earth. All shall love me and despair!"

As she says those things, we are told that she seems to Frodo "tall beyond measurement, and beautiful beyond enduring, terrible and worshipful." Yet, facing the moment of decision again, this time Galadriel makes a different choice than she had in the past long before. She turns from her ambivalent ambitions, from the temptation of power-- even with the good which that power might for a time bring with it-- and makes a choice that will in a sense undo the choice she had made so long ago, when she had chosen to go against the decree of the Valar in first coming to Middle Earth. Now, her decision to let Frodo keep the One Ring, if Frodo is successful in destroying the Ring, will mean that Galadriel will soon leave Middle Earth forever and return to face the Valar and, we would suppose, be reconciled with them. Frodo, although very learned for a Hobbit in Elf lore, does not know of Galadriel's own history, and to him she simply says, "I pass the test... I will diminish, and go into the West, and remain Galadriel." At that moment she is speaking as much to herself, I believe, as to Frodo.

And again, she seems to be speaking half to herself, when replying to Sam, who had said, "I wish you'd take his Ring. You'd put things to rights... You'd make some folk pay for their dirty work."

"I would," Galadriel tells Sam. "That is how it would begin. But it would not stop with that, alas!"

And now we are in a better position, I believe, to more fully appreciate the significance of what Galadriel says in that opening voiceover to the movie trilogy. When she talks about men's desire for power, she remembers her own desire for power. When she says that "all of them were deceived" she includes herself. She acknowledges to herself, and to any who still remember that long past history, or wish to learn of it, her own role in allowing the world to be twisted by Sauron from what should have been. And yet, as Galadriel introduces us to the tale in her voiceover, she does so with the knowledge that ultimately she passed the test and redeemed herself and her role in that history. Indeed, she can know of herself now that she held true to something she said to Frodo just before Frodo made his tempting offer to give her the Ring. What she said was that she wished "That what should be shall be... The love of the Elves for their land and their works is deeper than the deeps of the Sea, and their regret is undying and cannot ever wholly be assuaged. Yet they will cast all away rather than submit to Sauron: for they know him now."

Despite her perhaps undying, unassuageable regret for the loss of Lothlorien and her work in Middle Earth, I believe that Galadriel is comforted, consoled, and happy, having passed the test, stood true to her stated wish "that what should be shall be", and having returned at last to the undying lands, and to the presence of the Valar. I find an empathetic sense of consolation, and it is a picture upon which I like to gaze.

Of course there may be some inconsistency in having Galadriel narrate all of this, if she is already in the Undying Lands. Some of the other things she says in the voiceover may not make complete sense in that context. But I for one find the underlying meaning satisfying enough that I don't feel any wish to spoil it with textual criticism/analysis. In any event, this concludes for the most part a look at Galadriel in the familiar setting in which we are used to seeing her, the backdrop of LOTR and the Silmarillion. Now on to the Parallel Universe.

"Beautiful and terrible as the Morning and the Night... all shall love me and despair"

A Short Cut for those who tend to say to new books, "You had me at hello":

A distinct advantage available to anyone who sets out to read She and other books by H. Rider Haggard, is that it can be done for FREE. Dozens of Haggard's works are available for download from Project Gutenberg. Another free venue for reading Haggard is Google Book Search, where, if the search feature is set to "full view" mode, stories can be read in actual book formatting, which tends to be a little easier on the eyes than Gutenberg's plain text, minimally formatted files. Not quite free, but still very cheap, are etext versions available through Amazon for Kindle, a portable electronic book reading device.

Kindle Etexts of She and other Haggard books

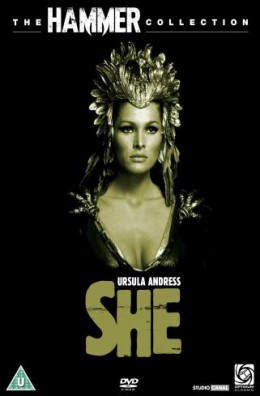

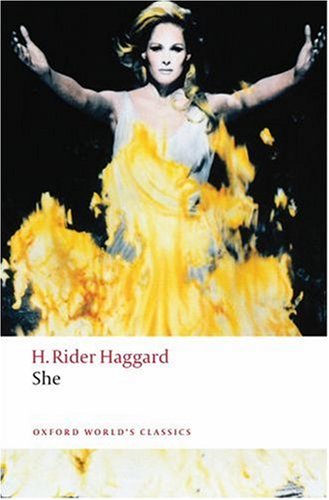

Ursula Andress portrays Ayesha in a Hammer film.

Did you know the origin of the phrase "She Who Must Be Obeyed", often used humorously these days, originated with Haggard's books?

- She Who Must Be Obeyed

Humorous t-shirts and other apparel, mugs, mousepads and other gift items, all with "She Who Must Be Obeyed" caption.

Galadriel in the Parallel Universe

I hope the above, especially if you've never read the Silmarillion before, opened the possibility of examining Galadriel in a somewhat different light. Even though we talked about things that might be considered flaws or frailties, yet they seemed, at least to me, to make Galadriel's virtues stand out more clearly. Something else that might make us appreciate and understand Galadriel even more, is to consider "What might have been." What might have been, that is, if she had accepted Frodo's offer to give her the One Ring, and if she had become "a Queen... beautiful and terrible."

Now, if you were hoping for me to unveil a lost work of J.R.R. Tolkien in which he developed the idea of a parallel Middle Earth with a beautiful but ultimately evil Galadriel, I'm afraid I must disappoint you (meantime, Tolkien purists will probably be heaving a grateful sigh of relief right about now). However, I have something which I think will be almost as good (translate "nowhere near as bad" if you are an extreme Tolkien purist). It is not a work of what is called "fan fiction" either, in which a Tolkien 'fan' uses established characters to write 'new chapters'.

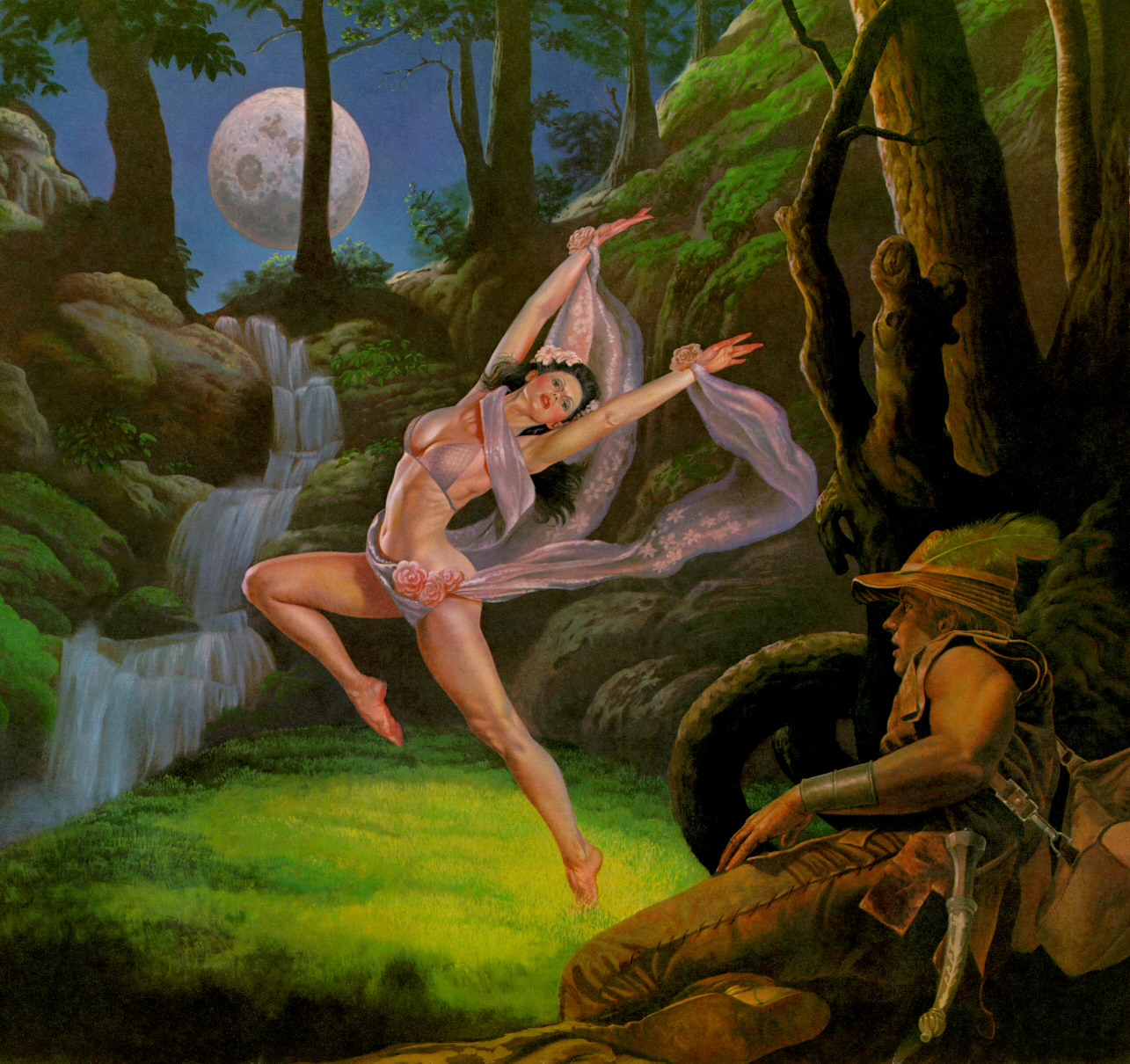

No, for our parallel universe we are turning to a work that has already been widely recognized as a literary influence on Tolkien; namely the book She, by H. Rider Haggard. In fact, besides numerous parallels that may be noted by the observant reader, between details that appear in Haggard's She and various works of Tolkien, Tolkien himself in a 1966 interview said that She had been an important book for him. Tolkien was not alone: many other writers of Tolkien's generation had grown up reading Haggard's tale and been left with a deep impression by it. This influence was not limited to writers of fiction. Carl Jung, whose theories of archetypes explored, among other things, the psychological resonance of literature through the collective unconscious, was deeply impressed by the literary character Ayesha, who is the 'She' to whom the title of Haggard's book refers. Jung used Ayesha as an example of what in his theories he called the Anima. I will make no attempt here to explain the Anima, but will simply suggest that it could be viewed as bridging-- and providing an interesting twist upon-- two ideas, which nowadays we often hear jokingly reduced to cliches. The first idea/current cliche is that of "a man getting in touch with his feminine side;" the second idea/current cliche is that of the stereotype of men fantasizing about women who -- to be conveniently circular-- are the kind of women who inspire stereotypical male fantasies. However, if you explore Jung's ideas of archetypes, and the anima/animus, as well as Haggard's character Ayesha, I think you'll find there plenty of food for thought which, far from reinforcing stereotypes, allows us to undercut and understand stereotypes, and certain other things, at a level far deeper than the merely superficial.

To return to my theme of Galadriel in a parallel universe, it is the character Ayesha that seems to me a candidate for consideration as a sort of alter-Galadriel, able to suggest very vividly what Galadriel might have become if the Elven Queen had chosen to accept Frodo's offer of the One Ring. I will try to strike a reasonable balance in providing some details to support this view, without committing undue amounts of plot spoilage for those who (I hope they are many) find themselves wanting to read She after reading this article-- if that is, they are not already personally acquainted with Haggard's book.

However, be warned that if even small plot spoilers have a tendency to ruin a story for you, turn now and retrace your steps to the portal by which you entered; go! Get thee hence, and return here, if ever, only when thou hast finished reading She.

She is recounted to us by a first person narrator, Horace Holly, usually referred to by others simply as Holly. Holly and his much younger ward and protege, Leo, pass through many eventful adventures before Ayesha ever makes her appearance in the book. Holly ends up becoming fairly close to Ayesha, and he sees firsthand many aspects of her personality and character. She--Ayesha-- excites in Holly feelings both of admiration and repulsion, but he finds that even the repulsion has a strangely irresistible attraction mixed in with it.

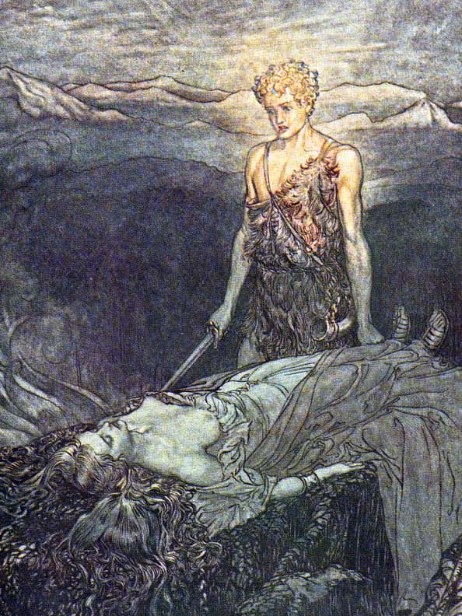

Remember for a moment how to Frodo Galadriel seemed "tall beyond measurement, and beautiful beyond enduring, terrible and worshipful," as she speaks of what would happen if she accepted the One Ring. Then let us look at how Horace Holly describes his first view of Ayesha's face:

"I gazed... at her face, and--I do not exaggerate--shrank back blinded and amazed. I have heard of the beauty of celestial beings, now I saw it; only this beauty, with all its awful loveliness and purity, was evil--at least, at the time, it struck me as evil. How am I to describe it? I cannot--simply I cannot! The man does not live whose pen could convey a sense of what I saw. I might talk of the great changing eyes of deepest, softest black... and [the] delicate, straight features. But, beautiful, surpassingly beautiful as they... were, her loveliness did not lie in them. It lay rather... in a visible majesty, in an imperial grace, in a godlike stamp of softened power, which shone upon that radiant countenance like a living halo. Never before had I guessed what beauty made sublime could be--and yet, the sublimity was a dark one--the glory was not all of heaven--though none the less was it glorious."

Even from that description of Ayesha's face, the reader will already begin to get a sense that Ayesha is, like Galadriel, an immortal creature of loveliness, wisdom, and power-- potentially very frightening power. "Like and unlike they are." In The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien could be said to have beat me to the punch, anticipated my little "Parallel Universe" conceit, and to have roundly trounced me at my own game, by masterfully presenting Gandalf and Saruman as 'parallel universe' counterparts of each other-- although, technically speaking, the two wizards were in the same universe. But I think you get my drift. Well, Ayesha and Galadriel present an observant and thoughtful reader with the opportunity to blaze a trail parallel to the one that Tolkien blazed in comparing and contrasting two individuals that are so much alike and yet so different.

Before we wade into deeper waters, we could make note of a more superficial, but still significant-- and to me sort of fascinating-- similarity between the accounts of Galadriel and the accounts of Ayesha. Galadriel allows both Frodo and Sam to gaze into the Mirror of Galadriel. Galadriel's Mirror is not made of polished metal or glass, but rather contains water as a reflective surface. When Galadriel pours water into the Mirror's basin, she can make more than just normal reflections appear. The Mirror can show to a viewer "things that were, and things that are, and things that yet may be." Galadriel tells Frodo and Sam that she can command the Mirror to show many things, and that it also will sometimes show things of its own initiative. Now, if we shift our gaze back to Horace Holly's account of Ayesha, we come to a really striking parallel to Galadriel, that emerges in the course of the following discussion between Holly and Ayesha:

'"Dost thou wonder how I knew that ye were coming to this land, and so saved your heads from the hot-pot?"

"Ay, oh Queen," I answered feebly.

"Then gaze upon that water," and she pointed to the font-like vessel, and then, bending forward, held her hand over it. I rose and gazed, and instantly the water darkened. Then it cleared, and I saw as distinctly as I ever saw anything in my life--I saw, I say, our boat upon that horrible canal. There was Leo lying at the bottom asleep in it, with a coat thrown over him to keep off the mosquitoes, in such a fashion as to hide his face, and myself, Job, and Mahomed towing on the bank.

I started back, aghast, and cried out that it was magic, for I recognised the whole scene--it was one which had actually occurred.

"Nay, nay; oh Holly," she answered, "it is no magic, that is a fiction of ignorance. There is no such thing as magic, though there is such a thing as a knowledge of the secrets of Nature. That water is my glass; in it I see what passes if I will to summon up the pictures, which is not often. Therein I can show thee what thou wilt of the past, if it be anything that hath to do with this country and with what I have known, or anything that thou, the gazer, hast known. Think of a face if thou wilt, and it shall be reflected from thy mind upon the water. I know not all the secret yet--I can read nothing in the future."

Although we may not nowadays accord Haggard with critical recogition on a level with that which is sometimes extended to Tolkien's work, this may be principally because of stylistic differences, as well as perhaps, the changes in public perception that usually occur over the passage of time. Both authors certainly present us with vivid ideas that can arrest our attention and galvanize our imagination. Notice in the passage quoted above how Haggard makes explicit something which is only implicit in Tolkien's description of Galadriel's mirror-- how interestingly the idea of a mirror is developed as Ayesha explains to Holly that personal knowledge or experiences of the viewer are reflected from the viewer's mind upon the surface of the water; a psychical or metaphysical mirror. Of course, this somewhat lengthy explanation does not sound out of character coming from Ayesha, who after all is rather condescending at times, to put it mildly. However, such an explanation by Galadriel to the hobbits would have been incongrous--jarring--out of synch in the milieu which Tolkien had constructed. However, we can enjoy as a bonus of this visit to the parallel universe this opportunity to have additional light shed-- possibly-- on why Galadriel used a mirror, of all things, to view 'otherwhen' and 'otherwhere'. It even seems that the significance of the mirror used by the Queen in Snow White gains additional depth after thinking along these lines. However, on further reflection (ha ha) we also see aspects of Galadriel's mirror that would not be explained by, or would even be contradicted by, the explanation given by Ayesha. No matter, for we will still have enjoyed thinking more deeply into the matter.

Despite many similarities, there are vivid contrast in the ways in which Galadriel and Ayesha are presented. Galadriel, almost as if she were an image in her own mirror, allows Frodo to glimpse for a moment herself as a dreadful, worshipful Queen "that yet may be," but which she does not become. And Galadriel does make each member of the Company face a sort of test or temptation as she looks into their eyes and seems to read their hearts. Yet we get a far different feeling from the way in which Ayesha interacts with Holly and others around her. Ayesha can switch in a heartbeat from a charm that enraptures the recipient of her attentions, to a terrifying display of passionate, yet icy, superhuman power. Holly tells of his own personal experience of one of these terrifying transitions:

"Suddenly she paused, and through my fingers I saw an awful change come over her countenance. Her great eyes suddenly fixed themselves into an expression in which horror seemed to struggle with some tremendous hope arising through the depths of her dark soul. The lovely face grew rigid, and the gracious willowy form seemed to erect itself.

'"Man," she half whispered, half hissed, throwing back her head like a snake about to strike--"Man, whence hadst thou that scarab on thy hand? Speak, or by the Spirit of Life I will blast thee where thou standest!" and she took one light step towards me, and from her eyes there shone such an awful light--to me it seemed almost like a flame--that I fell, then and there, on the ground before her, babbling confusedly in my terror."

I think we can get an inkling, a pale and insubstantial inkling, of what Holly is describing, if we picture the over-the--top behaviour occasionally adopted by our modern day pop culture Divas. This is not to make light of the Haggard's excellent and nuanced portrayal of Ayesha, and especially should not be confused as a sort of short-cut explanation of what Jung's aforementioned Anima concept meant. 'Diva' is not quite an archetype, at least not in my book, but I think it points in the right direction.

Another idea that is currently popular, which could help to give us an inkling of what is at the core of Ayesha's being, is that of the vampire. Of course, Bram Stoker's Dracula was to enter the collective conscious, and maybe even the collective unconscious, in 1897, fairly soon after the publication of She in 1886-1887. I don't know if Ayesha influenced Stoker's description of Count Dracula, but if you examine Stoker's story, and read between the lines a bit, you will find that Stoker characterizes the vampire as being ultimately miserable despite his provisional immortality-- even though unwilling to relinquish his undead existence, he nevertheless feels unsatisfied, perhaps trapped by it. I think we can see strong echoes of this in Haggard's portrayal of Ayesha, and perhaps even faint hints of it in Tolkien's delineation of certain aspects of the lives of Galadriel and other Elves. When Ayesha is, unawares, being watched by Holly at one point, this is how she appears to him:

"...her face was what caught my eye, and held me as in a vice, not this time by the force of its beauty, but by the power of fascinated terror. The beauty was still there, indeed, but the agony, the blind passion, and the awful vindictiveness displayed upon those quivering features, and in the tortured look of the upturned eyes, were such as surpass my powers of description."

Ayesha, we find, despite her power, beauty, knowledge, and apparent immortality, is not entirely happy-- in fact she often seems anything but happy. Well, for that matter, Galadriel herself told us that the Elves' "regret is undying and cannot ever wholly be assuaged." So, after all, what is the difference? Both are unhappy, aren't they? But I think, although it would be difficult to succinctly encapsulate in words all of my reasons for so thinking, that most people, after reading both LOTR and She, will feel that Galadriel's version of (limited?) immortality would be much preferable to the immortality of Ayesha, and in fact, that the comparison would be of the proverbial "apples and oranges" variety. Tolkien makes a comment somewhere to the effect that the beauty and wisdom of the Elves is actually enriched and deepened by their sorrow. Why does the same benefit not apply to Ayesha?

Actually, perhaps it does eventually. If you read Haggard's sequel to She, entitled Ayesha, the Return of She, you will find that Ayesha begins to seem more sympathetic and even seems to expend more effort to try to restrain her darker impulses. Whether she is able to escape from the tragedy of her lonely, quasi-vampirical immortality is something which the curious reader will have to wait until the final pages of that book to find out. Even if you only read She, I think Ayesha can be seen in a more sympathetic light if you consider that Ayesha provides us with a picture not just of what Galadriel might have become, put perhaps also indicating some of the interior processes that led Galadriel to originally defy the Valar and to undertake whatever part she played in the Kinslaying-- for it should be remembered that no matter how hard it might be for mortals to see beyond the fair exterior of Tolkien's Elves, the Elves' sensations, memories, and regrets associated with the Kinslaying, and with many another event of loss or suffering in their long history, may very well have been no less miserable than the tragic unhappiness which we more easily discern in Ayesha, who lacks the peculiar trans-mortal opacity characteristic of the Elves. Perhaps the parallel universes almost intersect at certain points, even though they are far apart at others. Perhaps the Ayesha that we encounter in Haggard's story is closer than we might realize to a snapshot of Galadriel, or certain aspects of Galadriel, in times long before the War of the Ring.

However, in some ways, even when viewed in the most sympathetic light, Ayesha and Galadriel would still seem very different, and incompatibly different. As an example, recall the statement which Galadriel made to Frodo, and to which she stayed true despite temptation, that she wished "that what should be shall be." Recall that simple, compact, but eloquent summation of Galadriel's better nature, her 'credo' if you will, and contrast it with the following rather dizzying explication/mini-lecture that Ayesha delivers to Holly, summing up her rather utilitarian, amoral views on life and power. It is really a rather interesting specimen of its kind, for it appears simultaneously to be tortuous-- full of devious twistings and turnings-- yet also straightforward and seductively logical. I have also included Holly's editorial thoughts in response to Ayesha's speech, with his nicely apt use of 'casuistry' likely to appeal (one way or the other) to those who enjoy ethical debates.

'"Is it, then, a crime, oh foolish man, to put away that which stands between us and our ends? Then is our life one long crime, my Holly, since day by day we destroy that we may live, since in this world none save the strongest can endure. Those who are weak must perish; the earth is to the strong, and the fruits thereof. For every tree that grows a score shall wither, that the strong one may take their share. We run to place and power over the dead bodies of those who fail and fall; ay, we win the food we eat from out of the mouths of starving babes. It is the scheme of things. Thou sayest, too, that a crime breeds evil, but therein thou dost lack experience; for out of crimes come many good things, and out of good grows much evil. The cruel rage of the tyrant may prove a blessing to the thousands who come after him, and the sweetheartedness of a holy man may make a nation slaves. Man doeth this, and doeth that from the good or evil of his heart; but he knoweth not to what end his moral sense doth prompt him; for when he striketh he is blind to where the blow shall fall, nor can he count the airy threads that weave the web of circumstance. Good and evil, love and hate, night and day, sweet and bitter, man and woman, heaven above and the earth beneath--all these things are necessary, one to the other, and who knows the end of each? I tell thee that there is a hand of fate that twines them up to bear the burden of its purpose, and all things are gathered in that great rope to which all things are needful. Therefore doth it not become us to say this thing is evil and this good, or the dark is hateful and the light lovely; for to other eyes than ours the evil may be the good and the darkness more beautiful than the day, or all alike be fair. Hearest thou, my Holly?"

'I felt it was hopeless to argue against casuistry of this nature, which, if it were carried to its logical conclusion, would absolutely destroy all morality, as we understand it. But her talk gave me a fresh thrill of fear; for what may not be possible to a being who, unconstrained by human law, is also absolutely unshackled by a moral sense of right and wrong, which, however partial and conventional it may be, is yet based, as our conscience tells us, upon the great wall of individual responsibility that marks off mankind from the beasts?'

We might also get a sense of a sharp contrast if we turn for a moment from Galadriel and instead compare Ayesha to Faramir. Faramir, you will remember, is stern in his own way, and makes decisions in matters of life and death, pronouncing 'dooms' upon travelers through the areas of Ithilien patrolled by him and his forces. He holds himself and others rather strictly to the laws that apply. Yet re-read all of what passes between Frodo, Sam, Smeagol, and Faramir; and then compare all of that to the very different impressions you will get from Ayesha's own pronouncements of doom and her own attitudes towards laws. Here is one sample, taken from Ayesha's words during one terrifying encounter with some of her subjects who have disobeyed her:

"Hath it not been taught to you from childhood that the law of She is an ever fixed law, and that he who breaketh it by so much as one jot or tittle shall perish? And is not my lightest word a law? Have not your fathers taught you this, I say, whilst as yet ye were but children? Do ye not know that as well might ye bid these great caves to fall upon you, or the sun to cease its journeying, as to hope to turn me from my courses, or make my word light or heavy, according to your minds?"

And here is another representative sample, when Ayesha is discoursing to Holly on her plans for the future with her husband-to-be, Kallikrates, and Holly voices an objection to the consequences of those plans, and how they would violate the law:

"The law," she laughed with scorn--"the law! Canst thou not understand, oh Holly, that I am above the law, and so shall my Kallikrates be also? All human law will be to us as the north wind to a mountain. Does the wind bend the mountain, or the mountain the wind?"

It would be possible to continue with more comparison and contrast of Galadriel and Ayesha, but I think that enough has already been set forth to indicate the potential rewards in store for the reader to whom a personally conducted execution of such comparison and contrast would hold marked appeal.

Another incidental bonus I'd like to mention is that for any of those who enjoy looking into a story for signs of the presence of the famed "unreliable narrator," She definitely offers plenty of raw material susceptible to such interpretations. An example would be editorial footnotes added to the text by Horace Holly himself. In at least one place, although he records his initial impressions of deep dismay at Ayesha's amoral and selfish philosophy of life, Holly tempers or emends his initial judgement in a footnote to the original text. Such a revised opinion could be interpreted as simply being the result of having additional time to think through and come to a more accurate estimation of Ayesha. On the other hand, it could be interpreted as Holly's original moral sense gradually caving in under the seductive weight of Ayesha's 'casuistry'. I suppose a third possible interpretation, although to me it would seem a bit overstrained, could be something along the lines of Holly gradually falling under Ayesha's 'spell' in a manner somewhat akin to the way Renfield fell under the remote influence of Count Dracula.

Interessante nota sobre a presciência das elfas. Posso concluir que Lúthien não viu apenas o "amor por Beren". Ela viu também o "futuro de seu amor com Beren".

Interessante nota sobre a presciência das elfas. Posso concluir que Lúthien não viu apenas o "amor por Beren". Ela viu também o "futuro de seu amor com Beren".