Neoghoster Akira

Brandebuque

...

"And where the wall is built in new

And is of ivy bare

She paused—then opened and passed through

A gate that once was there."

...

The Little Ghost - Edna St. Vincent Millay

O Poder Ora Fantasmagórico Ora Real das Palavras

Muito se pode concluir dos trabalhos apresentados por Verlyn Flieger e Owen Barfield para se explorar os conceitos e significados em uma obra como a de Tolkien.

Todavia também é verdade que ainda que o autor houvesse terminado de determinar e lapidar cada aresta dos livros de pouco lhe valeria se não fosse o poder de encantamento da poesia nos leitores.

Nos tempos idos do século 18, 19 e começo do século vinte quando as obras de referência a Tolkien foram escritas um tipo de poesia era muito popular entre as pessoas, produzindo um gênero que poderíamos chamar de "Poesia Sobrenatural".

Para quem estuda o assunto em Portugal nessa época, a arqueologia costumava dividir os estudos e reconstrução de textos e significados em uma dessas 3 categorias abaixo, especificamente a literária:

-Arqueologia Literária

-Arqueologia Artísitica

-Arqueologia Usual

Esta primeira categoria em específico se responsabilizava por organizar, estudar e guardar os relatos escritos, inclusive experiências religiosas e transcendentes de santos nas igrejas.

Afinal, depois de tantos séculos era necessário transmitir ao povo o poder da palavra nos relatos com o melhor da exatidão e fidelidade ao significado obrigando os sacerdotes a convocarem quem melhore entendia do assunto, escritores, poetas, músicos...

Eram então elaborados hinos e canções tradicionais, poemas e livros em torno deste tema.

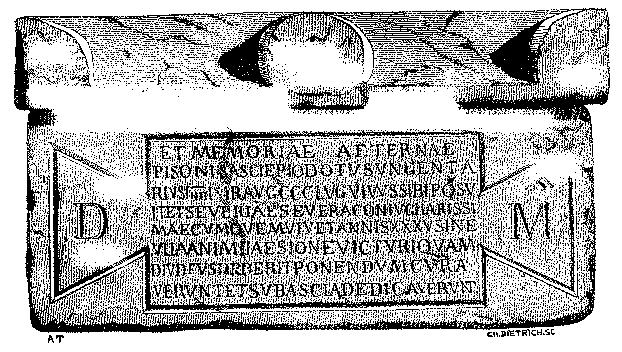

A partir dele (do tema) a obra literária inspiraria a construção de portais, portas, lápides, portões, túmulos... No ocidente e no oriente trechos destes textos foram então gravados em pedras, madeira e metal influenciando fortemente a literatura da época. Exemplos:

Primariamente com objetivo solene, tal poesia encantatória no ocidente teria origem e musicalidade mais misteriosa do que se costuma admitir conforme comenta esse trecho num blog de musicologia de um aluno da UCLA:

Teoria da Música Chinesa e Suas Implicaões para a Música Ocidental

Chinese Music Theory and Its Implications for Western Music

"Legend states that music in China developed when Huangdi (founder of the Chinese Empire) instructed a man by the name of Ling-lun to travel the Kwen-lun mountains. There he found bamboo shoots, and wishing to imitate the nearby birds in the forest of the mountains, he cut the bamboo into what would eventually create the chromatic scale (called Lü in Chinese) through blowing 12 different pitches. This legend is important to state as it gave birth to the belief that each tone in the Lü scale has specific ties to nature.

In the Lü scale, tones like the second tone Tai-tsoh represents rain and the awakening of insects and tones like the eighth tone Lin-tsong represents extreme heat and the beginning of autumn. The significance of this tie to nature is that every note in the Chinese Lü scale illustrates the great care Chinese theorists have approached music.

This is where I believe that the Chinese philosophy of music could help western scholars. Theorists in the west tend to have a scientific, mathematical approach to music theory, but there is little questioning why. They instruct music students to follow part-writing rules of harmony, the melodic rules of counterpoint, but the only explanation they have is “this is the way it is done, and we do not question that.”

Ou seja, academicamente se reconhece a busca de Tolkien pelas narrativas do tempo dos Heróis do mundo antigo, mas que existe também um importante elemento de elas terem emergido primeiro e ainda mais por amor a tipos específicos de encanto na poesia antes de vir por meio de decisões e soluções didáticas, editoriais e acadêmicas.

De que na imitação da natureza a letra criasse laços fortes com os significados do mundo indicando que Verlyn Flieger estaria realmente correta em reservar valor a semântica ao invés de unicamente focar nas regras.

No livro "A History of Japanese Literature, Volume 1: The Archaic and Ancient Ages" de Jin'ichi Konishi, se comenta que a antigüidade buscada por Tolkien não conseguia separar entre religião e literatura, entre a eternidade de um herói militar ou a eternidade buscada por um santo. O trecho:

"...

...there remained no distinction between religion and literature; both narratives and songs drew on Kotodama, the concept of words as incantatory and divine, so that poets no only transmitted meaning but a sense of the Supernatural.

..."

A obra de Jin'Ichi cita que tal condição posteriormente se tornou "dormente" na sociedade, fazendo as pessoas imaginarem que o valor que dão as palavras vem de uma escolha vazia, mas que na verdade precisa ter importância semântica e cultural e não apenas escolha técnica ou se tornaria num idioma artificial sem utilidade.

Reading the Miraculous Powers of Japanese Poetry

Spells, Truth Acts, and a Medieval

Buddhist Poetics of the Supernatural

...

The supernatural powers of Japanese poetry are widely documented in the literature of Heian and medieval Japan. Twentieth-century scholars have tended

to follow Orikuchi Shinobu in interpreting and discussing miraculous verses

in terms of ancient (arguably pre-Buddhist and pre-historical) beliefs in

koto-dama 言霊, “the magic spirit power of special words.” In this paper, I argue

for the application of a more contemporaneous hermeneutical approach to

the miraculous poem-stories of late-Heian and medieval Japan: thirteenth-

century Japanese “dharani theory,” according to which Japanese poetry is

capable of supernatural effects because, as the dharani of Japan, it contains

“reason” or “truth” (kotowari) in a semantic superabundance. In the first sec-

tion of this article I discuss “dharani theory” as it is articulated in a number of

Kamakura- and Muromachi-period sources; in the second, I apply that theory to several Heian and medieval rainmaking poem-tales; and in the third,

I argue for a possible connection between the magico-religious technology of Indian “Truth Acts” (saccakiriyā, satyakriyā), imported to Japan in various

sutras and sutra commentaries, and some of the miraculous poems of the late-Heian and medieval periods.

At some time in or around the fifth year of the Engi era (905), the Japanese court poet Ki no Tsurayuki wrote in his introduction to the anthology

Kokin waka shū古今和歌集 (Collection of Poems, Past and Present)

that Japanese poetry has the power to “move heaven and earth, stir feeling in

unseen demons and gods, soften relations between men and women, and soothe

the hearts of fierce warriors.”

1

His words are well-founded, for the literature of

premodern Japan abounds in tales of poets who have used poetry to a variety of

ends, including to inspire love, cure illness, end droughts, exorcise demons, and

sometimes even raise the dead. Contemporary scholars refer to such stories as katoku setsuwa 歌徳 説話, “tales of the wondrous benefits of poetry.”

...

De fato, "os miraculosos poderes da poesia" citados acima inspirando amor, curando doenças, secas, exorcizando demônios e levantando os mortos são usados em Tolkien em que cada ocasião apresenta e inspira certo tipo de emoção ou clima.

E de maneira semelhante, vários arquétipos e significados de Tolkien são condensados em uma única palavra criando uma força semelhante ao do Kotodama Japonês em trazer ao mesmo tempo razão e verdade encerrados em si durante passagens instigantes dos textos, a mesma força transcendente que move as pessoas. Ainda, segundo o autor acima, o poder do "verso" equivale a meditação e supera o valor da linguagem ordinária por meio de super abundância semântica.

Tanto poder dá uma dimensão diferente no entendimento do mundo primordial dos Valar aonde música e criação se misturam e não tem diferenças. A forja de Aulë seria acionada ao mesmo tempo com poder e com poesia.

Aos Poderes é dado lembrar da música primordial. A eles lhes compete possuir o que conseguiram guardar da música e serem possuídos por estarem dentro da manifestação dela enquanto trabalham.

A entrega honesta ao trabalho ao se tornar ferramenta de um bem maior trata de Aulë especificamente e o pesquisador acima fala do assunto quando comenta da necessidade de habilidade e coração sincero para comover os deuses do Japão com poesia capaz de mudar o coração das pessoas:

To move heaven and earth and stir emotion in demons and gods requires

both deep feeling and good poetry. However deep one’s feelings might be,

if one should write, “How sad, how sad,” demons and gods are not likely

to be moved. But if a poem is born of an earnest heart and is but skillfully

wrought, supernatural beings are sure to be moved of their own accord. Like

-

wise, however elegant the language of a poem, should that poem lack feeling,

demons and gods are unlikely to respond. But when people hear a poem that

is both profound in sentiment and gracefully crafted, their hearts are natu

-

rally touched. So too heaven and earth are moved and demons and gods are

affected.

...

In what way does a poem surpass ordinary language? Because it contains many truths in

a single word, because it exhausts, without revealing, deepest intent, because it summons

forth unseen ages before our eyes, because it employs the ignoble to express the superior,

and because it manifests, in seeming foolishness, most mysterious truth—because of this,

when the heart cannot reach and words are insufficient, if one should express oneself in

verse, the mere thirty-one characters [of a poem] will possess the power to move heaven

and earth, to calm demons and gods.

...

Para os grandes e para os pequenos a poesia funciona como "spell" nos personagens de Ea:

...

"Again she fled, but swift he came.

Tinúviel! Tinúviel!

He called her by her elvish name;

And there she halted listening.

One moment stood she, and a spell

His voice laid on her: Beren came,

And doom fell on Tinúviel

That in his arms lay glistening."

A evocação do nome de Lúthien, não é apenas poesia, ele encerra o significado de amor honesto, manifestado por sua aproximação de Beren. Nas palavras da letra da música oitentista Get Closer de Valerie Doré: "Changing a Spell Can Save You".

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Owen_Barfield

Song of Beren and Lúthien

http://tolkien.cro.net/talesong/s-berenl.html

Project Gutenberg

http://www.gutenberg.org/

Renascence and Other Poems

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/109/109-h/109-h.htm#ghost

NOÇÕES ELEMENTARES DE ARCHEOLOGIA

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/17186/17186-h/17186-h.htm

Reading the Miraculous Powers of Japanese Poetry

https://nirc.nanzan-u.ac.jp/nfile/2859

Teoria da Música Chinesa e Suas Implicaões para a Música Ocidental

https://mixolydianblog.com/2012/07/14/chinese-music-theory-and-its-implications-for-western-music-2/

A History of Japanese Literature, Volume 1: The Archaic and Ancient Ages

https://books.google.com.br/books?id=k4orDgAAQBAJ&pg=PA61&lpg=PA61&dq=supernatural+poetry+japan+kotodama&source=bl&ots=qqlHfD_PQf&sig=eunVK5FIZDKq21xiReJBnIjGZnc&hl=pt-BR&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjzw5DlxvXSAhVFlpAKHTy-ChMQ6AEIOTAE#v=onepage&q=supernatural poetry japan kotodama&f=false

Última edição: